“A situated love of nature is not merely loving a place, but rather loving the Earth by loving a place.” – L. Candiotto

“We accept that the protection of the remaining old-growth trees and forests is more salient to human well-being than harvesting timber to meet our immediate needs.” – Julie Nielsen, on David Ellingsen’s website

September clouds drift with summer’s exhalation as we walk in sunshine along the old Wellington railroad grade between the sites of Number One Japan Town and Cumberland Chinatown. Gnarly apple trees rise from goldenrod meadows past their prime. It’s so quiet. Raven’s quoark in the distance sounds like a zenmokugyo. Three female mallards drift by on the pond, the last one makes a half-hearted effort to snag the dragonfly that flits past her. A couple of locals fish for the invasive American Bullfrogs (“got six yesterday, lost three today so far”). On the wooden footbridge that commemorates the commerce between the two town sites, a striped meadowhawk dragonfly lands on my hand to investigate, or simply rest.

In 1888, this was a bustling place. The path we walk upon linked several mine sites. At its peak, the population of Chinatown may have been as much as 3,000. The first Chinese had arrived in B.C. in 1858, heading for the gold fields. The first Japanese settler (Manzo Nagano) arrived in 1877. The Depression resulted in the demise of a Black settlement in 1931. The residents of Number One Japan town were shamefully interned in 1942.

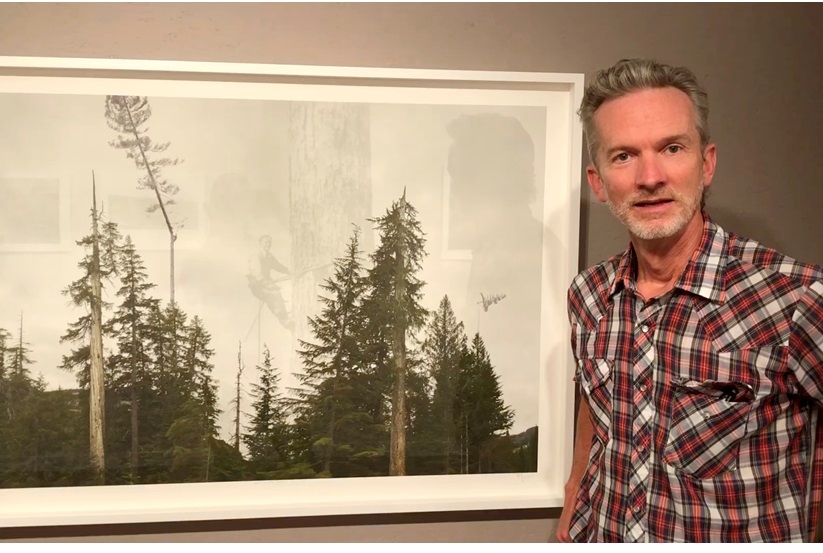

Now, nothing remains but a single log building – “Jumbo’s Cabin” – variously used as a lock-up, an ossuary, and a residence, purportedly hewn by a Finnish logger. The forest is mixed – big leaf Maple, Douglas Fir, willows, cottonwood, cedar in the shadows – and the wetland is being reclaimed and converted by beaver. Walking along, I reflect on my recent conversation with photographer, David Ellingsen, at his show Falling Boundaries, at the Old Schoolhouse Gallery on Cortes.

David was born and raised on Cortes, the grandson of one of the earliest settler families on the island, a logging family. Though we were both born in B.C., we spoke of our shared histories on this coast, both of us, as recent arrivals, just off the boat in relation to the indigenous inhabitants who have been here from “the beginning”, at least 13,000 years in “our” reckoning. As children, we both grew up inhaling the same smells, the smells of the Salish Sea, and the duff of the floor of second-growth forests. David: “as a child, I never realized that it had already been logged once. Like all of Cortes, all second growth forests and there are some pretty beautiful forests around here – but that, in concert with the beach, which was for days on end our baby-sitter in the summer time. Mom would just send us down to the beach and that was it and off we’d go and come back for lunch and off we’d go and come back for dinner and so for me, that land was really about connection, and what a gift I got from that! Being raised in a place like that! That was our home! Was the Land. And the Ocean and the Beach and all that stuff there, so…it’s more of a general overall feeling, the Land as an entity.”

Speaking the evening before, as the half-moon rose into the sky, he had summarized in some detail his journey from professional “photographer” to “artist who uses photographs as his medium.” In that talk, David framed his work as a grappling with the experience of solastalgia, the emotional or existential distress caused by environmental change. All of us at this moment, it seems to me, suffer from this distress; or we drift into a crevasse of denial and numbing, and attempt escape by whatever means available. Vanessa Andreotti identifies four denials that constitute modernity/coloniality: the denial of systemic, historical, and ongoing violence; the denial of the limits of the planet; the denial of our entanglement with the wider metabolism of the earth, the cosmos and the other-than-human; and the denial of the complexity and magnitude of the problems we face.[1]

The photographs that comprise the exhibition are palimpsests of sorts, in which the imperiled forests that we currently inhabit are juxtaposed with archival images of historic logging activity. Three small videos with the artist commenting are embedded to give a sense of the work:

That his family is a logging family makes the work both intensely personal while simultaneously cultural and public. The resultant mash-ups embody the complexity of our relationships with this place. We are invited to respect and honour the heroic labour of our ancestors and simultaneously grieve the losses that the land and its indigenous inhabitants have sustained. We are reminded of Gary Snyder’s poem, Dusty Braces, in which the “ancestors/ lumber schooners/ big moustache/ long-handled underwear/sticks out under the cuffs…you bastards/ my fathers/ and grandfathers, stiff necked/ punchers, miners, dirt farmers, railroad men/ killed off the cougar and grizzly”, are offered nevertheless, “nine bows. Your itch/ in my boots too,/ your sea roving/ tree hearted son.”

Viewers leaving the exhibit typically struggled to find easy and coherent responses. The photographs invite engagement, demand response and wobble the force of denial. The work upsets, evokes a confrontation with the aforementioned solastalgia, an experience of loss that evokes grief.

I imagine that solastalgia is grounded in and conditioned by our childhood entanglement with the places we inhabited in our earliest years. As children optimally freed to explore the places we inhabit do we not become “native” to a place? And might it yet be possible to discover or regain a life giving, animistic or pantheistic relationship with the places we inhabit? Philosopher Laura Candiotti suggests that the resulting “enchantment is not an ecstatic and sudden feeling of being connected to a place. As I said before, it is necessary to inhabit a place, to become its native, in order to start listening to it. This means that enchantment is not just a feeling but an attitude of experiencing the place differently. It has to do with a change in how one experiences the place, experiences oneself in the place, and experiences the relationship with the place. Becoming native to a place is thus a transformative practice.”[2]

She continues, “Arguably, I cannot speak with a tree as I speak with a fellow human, for example. However, maybe I can communicate with it if the tree is the tree I love, with whom I have a special relationship because we inhabit a shared place and I have undertaken a process of becoming its native….

This is the case when, for example, one encounters a river and becomes aware of its pollution and how much this is an effect of the destructive behaviours of humans in the exploitation of a resource. Therefore, the generative tensions are not only the ones that arise from difference and can lead to the acknowledgment of mystery. They are also the ones that come from a story of violence and that push us to do something to change what is considered wrong. In this case, the devastation of the planet is instantiated in the pollution of the river.”

This push to change what is wrong is central to David Ellingsen’s work. It is a testament to the hope and belief that our actions can still make a difference, despite the odds. Hearing of David’s passion makes me think of a recent article in Dark Mountain. In his essay, What Use Is Art, author Mat Osmund, “considers the disabling rhetoric of emergency, the role of art as a ‘life-cherishing force’ and what it entails to “hold ourselves accountable to a generation facing catastrophe.”[3]

He writes, “these stories about anthropogenic ecological collapse clearly matter: they occupy us, in both senses of that word, shaping for better or worse our notions of what ‘responding’ actually requires of us. And it’s into this contested space that activism, art and education all enter the fray – for better or worse. Of the stories now circulating within and among us, the one that keeps catching my ear – one I now hear voiced by both children and adults, by professors of ecological, climate and social sciences, by writers and artists, by exhausted activists and by their sneering online hecklers – can be spoken in three words. It’s too late.” He addresses here the notion, even the felt sense, that we are out of time.

One thing that I love about David’s work in this show (building upon and expanding previous exhibitions) is what happens to time. I mention to him that his work has a way of inviting those of us who grew up on this coast into our memories of the forest. Is this intentional? He confirms that by using the intersection of his own family history with that of the history of logging on the cost he hopes that the viewer will ask herself, “what’s my own experience, what’s my story?”

He says, “I really endeavour to inject this into all my work, that it’s not about me per se –I’m trying to use the construct or archetype of family structure and how that works throughout history and see what happened generations ago and what happens now and that didn’t work very well but at the same time, I’m still seeing the benefits of this three generations later – my mind wanders around those kind of ideas.”

So then, I think of summers at Robert’s Creek playing above the beach, among the remains of the old skid road that ran through our yard, and the stumps in the forest behind the cabin. Time then, in a sense, while collapsed, remains with us. We remember our ancestors, those who occupied these stolen lands. Shall we continue to repeat their mistakes, or shall we find and craft a different way? David’s photos enable us to clearly see the ghosts that inhabit these forests of these coasts, both historic and current.

In Hospicing Modernity, Vanessa Andreotti has created several ‘entity maps’ that enable one to chart a course through these turbulent times. The purpose of these “maps is ‘not to represent something already visible, but to do work in the world by surfacing what is unconscious, invisibilised, and naturalized, and moving things within and between us’. In this sense, she tells us, the evolving map invites us ‘into an aesthetic experiment where we can un-numb and activate other senses in order to experience reality in a different way – intellectually, affectively, and relationally’.

I believe that David’s Ellingsen’s work provides an elegant response to Mat’s question. In his essay, he quotes Mary Oliver, who suggested that poetry is a “life-cherishing force, providing fires for the cold, ropes let down to the lost.”

Whether you catch the work in exhibition or on line at David’s website (https://www.davidellingsen.com) you are invited into a relationship with the living forest, the forest of the past and the present, but most critically the responsibility for its future.

As David puts it, I’m just motivated to try – essentially that’s all I’m really doing, it’s just trying to contribute to some kind of positive momentum in the direction where I can make a difference…a tiny little infinitesimal scratch. I come from, you know, my Dad, and talk about someone who’s made a difference in his community – I mean who works for 25 years on one thing? – and sees it through, I mean the community forest – yes, there’s the board and the partnership and everything but he was one of the pivotal members of that and I think about that all the time and there that’s about the local community and getting back to Rex (Weyler) – that’s what he says, really the changes that need to happen now are really in local communities and that’s the only thing that’s going to have any effect at this stage of the game. My elders have spoken.

References:

[1] Machado de Oliviera (Andreotti), Vanessa: Hospicing Modernity, p. 23.

[2]Candiotto, L., Loving the Earth by Loving a Place: A Situated Approach to the Love of Nature.

[3]Osmond, Mat, What Use Is Art? https://dark-mountain.net/what-use-is-art/