Corporate Social Responsibility in Canada:

Trends, Barriers and Opportunities

March 2019

By: Coro Strandberg, President

Strandberg Consulting

Acknowledgements

This paper was researched and written with the generous support of others. In particular, I would like to thank the 32 companies that participated in the interviews and/or provided written submissions to the questions.

I would also like to extend my gratitude to members of the Community Development and Homelessness Partnering Directorate (CDHPD), Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), for their significant support for drafting the interview guide, identifying interviewees, conducting the interviews, aggregating the notes and undertaking the initial analysis of the notes and synthesizing the information. I extend my specific appreciation to Greg Graves, Manager, Sharmin Mallick, Policy Analyst, William Chen, Analyst, Luke Hansen, Senior Policy Analyst, Maurice Dikaya, Analyst, and Maya Nightingale, Analyst.

This project received funding from the CDHPD of ESDC.

About the Author

Coro Strandberg is a recognized national leader in corporate social responsibility and social purpose. For thirty years she has advised business, governments and industry associations on strategies to achieve social and environmental outcomes in the marketplace. She specializes in social purpose, the circular economy and sustainable governance, human resource management, risk management and supply chain management. With 20 years of experience as a corporate director, Coro educates corporate directors and governance professionals on sustainable governance for the Director’s College and Governance Professionals of Canada respectively. In 2015 she was named one of Canada’s Clean50 as the top CSR consultant in Canada for her impact. She publishes her thought leadership on her website at www.corostrandberg.com.

Executive Summary

The Federal Government wants to understand trends and best practices in corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the roles it can play to accelerate and advance CSR in Canada. It interviewed over 30 companies with CSR programs in the fall of 2018, from across the country. Interviewees represented large and small companies, including multi-national corporations, from a diverse range of sectors. Participants were from publicly traded, private and co- operative companies, excluding Crown corporations. Nearly half of the companies indicated they had, or were developing, a social purpose or mission to state the reason for the company’s existence – a purpose beyond profit. The company representatives interviewed were primarily in senior CSR roles. This was a qualitative study to identify general trends and directions in CSR in Canada.

The research revealed most respondents had a formal CSR approach, including goals, targets and metrics embedded in a CSR strategy. It found there was a continuum of CSR practices among the respondents from a community investment focus to a social purpose business model. Companies identified a shift in their CSR style over the past five years from ad hoc, incremental and transactional approaches, to strategic, social purpose-driven and transformational models. CSR is undergoing a transition from “nice to do” drivers to “essential for business success” motivations. Further, several companies did not use CSR terminology and saw it as an out-dated and irrelevant term.

Companies are also evolving their relationships with their community partners. There appears to be a continuum of practices from grant-based relationships on one end, to embedded models at the other, in which the non-profit operates out of the business. Some companies create their own partnerships and charities to advance their social goals. There are a range of motivations for partnering, from it being the right thing to do, to recognizing that the company cannot achieve its social purpose on its own and needs partnerships to foster innovation and achieve success. Companies which have advanced on the partnering continuum seek other companies to partner with, and notice that peers and competitors can be reluctant collaborators, as they seek competitive or marketing benefits only available through exclusive arrangements with non-profits. Companies expect to be involved in more long-term proactive, strategic partnerships in the future, in which they address systemic issues with non-profit organizations and others. A barrier to this evolution is distrust of business within civil society, and a lack of capacity within non-profits, including knowledge of how to partner effectively with business.

Interviewees spoke to their efforts to leverage intermediaries to help them advance their social innovation and social purpose goals. There are diverse approaches to working with intermediaries: some companies are intermediaries, others leverage their partnerships as intermediaries, some partner with their intermediaries and others fund them. There were very few reported instances of the use of intermediaries to access non-profit partnerships.

There was unanimous agreement that the government should play a lead role to accelerate and scale CSR in Canada. Two top ideas surfaced on its role: 1) the Federal Government could convene multi-stakeholder collaborations with the private and non-profit sectors to address priority issues, develop national social goals and a campaign, and possibly develop a national CSR strategy; and 2) it could create incentives to encourage take up, including recognition programs and awards, financial and tax incentives, social innovation challenges and government CSR procurement. One cross-cutting finding speaks to the importance of impact measurement, and the desire for the Federal Government to support national efforts in this area.

This qualitative study on CSR trends and best practices identifies a profound shift in how CSR is being practiced in Canada. CSR appears to be at an inflection point, in which the Federal Government can play a lead role to catalyze social and business success in the years ahead.

Introduction and Purpose of Research

The Federal Government’s Community Development and Homelessness Partnerships Directorate’s Horizontal Policy Unit within Employment and Social Development Canada conducted a study to scope out the current state of the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) field in Canada to determine key trends and best practices. The project sought to enable the Government of Canada to identify ways in which it can accelerate and advance CSR in Canada.

For the purposes of the project, CSR is defined as a company’s approach to improving its social and environmental performance and impacts. This study is particularly interested in a company’s community impact, relations and partnerships, including social innovation.

Methodology

In November 2018, representatives from 32 companies known to have corporate social responsibility programs were interviewed by the Federal Government (one submitted its response in writing). See the list of companies at Appendix A and the Interview Guide at Appendix C.

An effort was made to include a diverse range of businesses from across Canada, including large and small businesses with provincial and sectoral representation and national and global companies operating in Canada.

Nearly half (14) of the companies represented in the study are based in Ontario, with 11 from BC. Four are from the prairie provinces, two from Quebec and one from the Atlantic provinces, specifically Newfoundland and Labrador. None are from the territories. Two-thirds of interviewees (24) are from large companies and one third (8) are from SMEs (small and medium-sized companies with under 500 employees). Six are global multi-national companies.

The financial services sector was represented by nine respondents (about one-third). Other sectors include Retail (5); Manufacturing (4), Real estate (4), Technology (3), Services (3), Food (2), Energy (1) and Health (1). Some notable sectors missing from the research include the Resource and Entertainment/Travel/Tourism sectors.

The corporate structure was evenly distributed, with 12 publicly traded companies, 13 privately held companies and seven co-operatives, including credit unions. The research intentionally excluded crown corporations or government owned and operated entities.

Almost half of the companies (14) indicated that they had, or were developing, a social purpose or mission as the reason for the company’s existence – a purpose beyond profit.

A total of 36 people participated in the interviews, holding the roles of CEO (2), VP (4), Director (19), Manager (9), and Specialist (2). Over two-thirds held senior leadership positions (director level and up). One-third held “sustainability” titles (12); eight have community investment, corporate citizenship or philanthropy roles; seven have titles related to CSR. Other titles included “social purpose”, “community performance”, “impact”, “shared value”, “social innovation”, and “environment.” A small number held titles suggesting a more generic position (e.g. Legal and External Affairs) or unique roles (e.g. values-based banking).

This report is a qualitative study designed to assess the state of play of CSR. As such, interviewee responses are analyzed for general themes. The sample size does not support the drawing of definitive conclusions and the making of findings on statistical significance. However, the number and diversity of responses enables an overall assessment of CSR practices and opportunities in Canada.

Findings

Question 1: Current Approaches to Corporate Social Responsibility and Ground-Breaking Initiatives

Companies were asked to provide a brief overview of their current approach to CSR, along with any examples they viewed/perceived as ground-breaking, novel or innovative.

Highlights:

Most companies have a formal CSR approach, including goals, values, targets, and metrics, which are embedded in a CSR strategy. However, it is important to note that a number of companies do not use the term CSR to describe their efforts. Companies that don’t use CSR terminology answered this question from their non-CSR perspective.

There appears to be a continuum of “CSR” practices among the respondents, from a community investment focus, to a CSR strategy, to CSR integration and to social purpose. This would indicate that there is a trend to companies developing and integrating a social purpose into their business models. For a number of companies, CSR is seen as an outdated and no longer relevant term.

Using the language of CSR, eleven features were identified as indicative of the different CSR approaches, including:

- CSR board governance, strategy, embedment and reporting

- Social purpose business models

- Aligning CSR to the business

- Long-term CSR ambition to 2030

- Engaging the value chain and industry on CSR

- Thought leadership on CSR

The range of community investment practices described by interviewees included donations, sponsorship, in-kind, surplus good donations, employee and skills-based volunteering, customer enabled and product-based giving, matched donations, cause-marketing and flagship/signature programs.

Asked to describe innovative and ground-breaking examples of their CSR approach, companies spoke to developing inclusive business models, generating social impacts from their products, leveraging non-profit expertise in product design, setting industry benchmarks, government collaborations, engaging competitors and business customers on social innovation, and generating social good from technological applications.

Detailed Findings:

Most companies have a formal CSR approach, composed primarily of goals, targets and key performance indicators or metrics. Nearly all of these are embedded in a formal CSR strategy. A smaller number indicated they have a CSR policy. A small minority did not have any of these formal practices.

Eleven features were observable from the description of the companies’ CSR approach. They are summarized in the following table.

| Feature | CSR Approach |

| CSR

governance |

Board governance and oversight of the company’s social and environmental

commitments, including a board sustainability committee |

| Social

purpose |

Articulation of a social purpose as the reason for the company’s existence

which infuses the business model |

| CSR strategy | CSR vision, values, policy, principles, strategy, goals, targets |

| CSR

embedment |

Embedment into corporate strategy, every business unit and decisions,

culture, international operations, risk policies |

| Aligned to

business |

Underpins business model and business plans; aligned to the company’s

purpose and its business imperatives; industry relevant, customer-centric |

| Long-term

ambition |

Long-term sustainability strategy to 2030, with ambitious visionary goals |

| Value chain | Addresses impacts along the value chain, up- and downstream of operations;

addresses supplier and supply chain impacts; ensures suppliers are sourcing and producing responsibly |

| Industry

standards |

Adheres to standards and certifications, e.g. UN Global Compact1, B Corp2,

Equator Principles3, Global Alliance for Banking on Values4, Fitwel5 |

| Reporting | Reports on CSR progress and impacts |

| Thought

leadership |

Provides thought leadership in the industry and society |

| Community investment | Community investments includes donations, sponsorship, in-kind, surplus good donations, employee volunteering and skills-based volunteering, customer enabled and product-based giving, matched donations, cause- marketing, flagship/signature programs |

- https://www.unglobalcompact.org/

- https://bcorporation.net/

- https://equator-principles.com/

- http://www.gabv.org/

- https://fitwel.org/

In addition, a few companies spoke to their decentralized approach to CSR, in which CSR direction is determined corporately but decisions are made locally. One company spoke to their approach to setting CSR priorities, which was to take long-term societal trends into account. Another described the maturation of their CSR program over 10 years, from a focus on getting their house in order, becoming a catalyst for a sustainable society, to embedding sustainability fully into the organization. As well, a few companies mentioned their intent to follow a triple- bottom-line approach to CSR, in which social, environmental and economic impacts and objectives are taken into account.

Notably, a significant minority commented that they don’t use the term CSR and think it is an outdated approach: “CSR as a term is outdated”; “We consider ourselves post-CSR”; “We don’t use the term CSR, our approach is to take the lens of sustainability”; “We use Environment, Social, Governance”.

Finally, a number of companies indicated they have adopted a social purpose as the reason they exist and build their social purpose into everything the company does. Those that have done so are most likely to say they don’t use CSR terminology. They view social purpose as a more holistic approach to the business, in which the business model is infused with their social intent and not treated separately.

These findings suggest a continuum or pathway of CSR practice, as demonstrated in the figure below:

CSR Continuum

| Level | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 |

| Focus | Community investment | CSR strategy | CSR integration | Social purpose |

Almost half of the companies appeared to be at level 4: they indicated that they had, or were developing, a social purpose or mission as the reason for the company’s existence.

Innovations and ground-breaking examples

Interviewees described a number of CSR innovations and ground-breaking examples:

- Inclusive Business Models: Designing inclusive business models in which companies work to include vulnerable populations (e.g., as suppliers or product distributors), and help the company enter hard-to-reach markets or access scarce resources; seeking to have products accessible to underserved (vulnerable) segments of the population through low-cost or free services

- Social Products: Leveraging products to contribute to the social goals; having products which enable social progress and are 100% sustainable; partnering with non-profits and non-governmental organizations to design socially useful products; having products which have sustainability targets which are robust, evidenced- based and internally verified

- Industry Leadership: Setting an industry benchmark; establishing bold goals that were adopted by other companies; developing and sharing tools such as a social purpose gap assessment tool that defines best, leading and next practices in social purpose and corporate social responsibility to assess progress and address gaps

- Collaboration: Collaborating with all levels of government, and with the industry (including competitors to advance social innovation)

- Customer Engagement: Sharing social innovation with business customers and encouraging their engagement

- Social Technology: Inventing new technologies that can be used for social good and partnering with government and community groups to make the technology available (“We want to understand who will and will not have access to technology”)

Company Profile:

“Our approach to CSR is centered around our company’s purpose. We have three areas of focus, and we feel that if we source our products responsibly, protect the environment and from across Canada, then we feel we can contribute positively to Canadians’ lives daily and in the future, and in the products we provide. We prioritize things within those three pillars: environment, sourcing and community. We look at urgency of the issue, relevance to our company, can we actually move the needle and the needs of our consumer. We have several inputs too: we look at benchmarking, look at what our competitors are doing, we look abroad as well, and we do our own CSR research every day, and with our customers and the customers of our competitors. We combine that with our strategic business imperatives and long-term trends. We post our results online, and we message through press releases and signage up in stores, etc. That’s how we communicate to our consumers.”

Company Profile:

“Essentially, our purpose is not to earn profits and then do good social projects. We want to earn profits by doing good things in the first place. Our purpose is to grow prosperity. In this way, everything we do needs to be good for the customer, the environment, and society. We think of ourselves as a social enterprise, which is not just a term for non-profits.”

Company Profile:

“We haven’t used the term CSR for a long time. We are a social purpose business. The difference between a social purpose business and a business with a CSR program is that a CSR program is bolted on. CSR programs thus have an indirect connection to the business whereas social purpose businesses have mechanisms that address social purpose holistically. All our programs are tied into supporting that social purpose which is generally geared towards improving the community or society and that’s how we operate. Our social purpose is linked into our mission and our value statement, the overlap is pretty much the entire thing. So, everything is aligned that way.”

Company Profile:

“We are a hybrid organization that is part cooperative and part free enterprise, so we are not capitalist in our approach. We consider ourselves to be a meritocracy and take a shared-value approach. Using the Mondragon Corporation (a federation of worker cooperatives based in the Basque region of Spain, founded in the town of Mondragon in 1956 by graduates of a local technical college) as our model, we are an employee cooperative founded on social justice principles and aim to generate both profit and social responsibility.”

Question 2: Recent CSR Shift

Interviewees were asked if and how their company’s approach to CSR has shifted in the past five years.

Highlights:

CSR is a very dynamic undertaking. Most interviewees commented on how their companies’ approach to CSR had shifted in the past five years.

Main shifts include a transition from ad hoc, transactional and incremental approaches to those which are strategic, holistic, social purpose-driven and transformational. Other top shifts include a focus on integrating CSR into the business model, a shift away from CSR strategies to social purpose business models, and a shift to becoming data-driven and actively measuring, tracking and disclosing social impacts. There is a shift from thinking of CSR as the social responsibility of business, to a way of doing business, and along with that a shift from thinking of CSR as a “nice to do”, to CSR is “essential for business success”.

Companies are starting to mature in their stakeholder engagement programs, from using their balance sheets for good, to identifying ways to advance their business so that society benefits as well and collaborating for social impact, to using industry CSR standards to determine CSR priorities.

Community investment approaches are undergoing transitions as companies learn from their early experiences: they are leveraging more resources than just grants and employee volunteering and looking to partner strategically with non-profits on higher-impact efforts.

Detailed Findings:

Most responded that their CSR approach had shifted in the past five years. Some spoke to the past approach and how it had transitioned to the current model, as set out in the table below:

| Approach | Past | Present |

| Measurement | Donations only, no strategy, measurement or partnerships | Strategy, metrics, targets, partnerships |

| Strategy | Scattered and ad hoc | Strategic |

| Comprehensive | Philanthropic | Holistic |

| Purpose | Corporate citizenship | Social purpose business model |

| Impact | Transactional | Transformational |

Some commented on the drivers of the shifts, which primarily included a greater focus on stakeholders, more stakeholder demand, and impact evaluations.

Only one mentioned how the company hadn’t undergone any shifts, and another person mentioned they were too new to comment on past shifts. A few commented that the shifts were still underway and were not final or complete. A few observed that the shifts were not substantial, but rather continuous improvement and a change in priority (see text box for an example of this).

Shifts

The top shifts identified in declining order of mentions are a shift to integrating CSR considerations throughout the business, a shift to developing and implementing a social purpose, a shift to becoming more data-driven, and a shift in community investment practices. These shifts are described below, along with other shifts mentioned by the interviewees.

Integration: Companies are embedding sustainability into all their business decisions. “It is no longer separate but integrated into corporate strategy, so it is not on the side any longer, but how we do business.” Companies are including CSR in the roles of HR and finance and other functions. One is integrating CSR in its annual report, so that it reports on financial and non- financial results in one disclosure. Another is including its CSR priorities in its project portfolio and risk register (see text box for more details).

Company Profile:

“To ensure holistic development and sustainment of physical assets, we created processes that aim to incorporate environmental and social aspects such as water use, air emissions, energy use, human rights, and stakeholder and Aboriginal relations into new projects. The purpose of sustainability integration into our process for developing physical assets, is to ensure: environmental and social risks are identified as part of the project definition, development options are evaluated against environmental and social risks through the concept selection process, environmental and social risks are incorporated into the project’s risk register, and our project portfolio is in line with our strategic sustainability goals and vision over the long-term.”

Social Purpose: A number of companies are developing and implementing their social purpose

– the company’s humanitarian reason for being – and using this to set their social priorities.

Data-Driven: A number of companies are taking a data-driven approach, improving the ways in which they track, measure, and collect data, and using data management to inform their CSR strategy. Related to this approach, companies are measuring the impact of their work and increasing their CSR data collection.

Community Investment: A few companies commented on the shifts they had seen in their community investment efforts. This included a shift from pro-bono work to providing grants, a shift from grants to more strategic hands-on partnering, and to providing greater access to resources such as space, employees and other assets, and a shift from supporting many non-profits in a non-impactful fashion to partnering with a reduced number of non-profits on higher impact activities.

New Focus: There was reference by some to a new focus on carbon, to greater board oversight of climate change, to becoming carbon positive (taking carbon from the atmosphere, rather than simply reducing the company’s carbon footprint) and to setting more ambitious carbon reduction targets. On the social side, one company spoke to a new focus on health and wellness of its employees and customers.

CSR Budget: A few companies mentioned how they now had a CSR budget and funding, which resulted in them moving away from ad hoc measures to becoming more strategic.

CSR Intent: A few companies commented they had identified what they stood for, which resulted in an increase in intentional giving and partnering than in the past.

Other shifts included:

- Set targets and benchmarks: “In the past we used to be very best practices based, but nowadays, we’re focused on our targets and how we meet the metrics we’re trying to target”

- Further alignment of social innovation to their business objectives, so that it is “more than a responsibility, but a way of doing business”

- Decentralization: “We are moving from a centralized to a decentralized approach to CSR and will continue to do so as it has been successful in achieving greater positive social impact”

- Company-wide recognition that CSR is not a “nice to do” but is required for business success and performance

- Maturation in stakeholder engagement and degree to which the company addresses stakeholder needs

- Shift to using balance sheet for good: “We realized that we have a lot more ability to make a difference if we use more of our balance sheet; we recently carved out a portion to start impact investing”

- Shift to a “shared value” approach, in which the company looks for ways it can benefit society while it invests in measures that benefit its business. In this way, shareholders profit when the company benefits society

- Shift to greater collaboration on social impact

- Started using a global industry standard to assess practices and identify gaps; this is being used in conversations with senior management

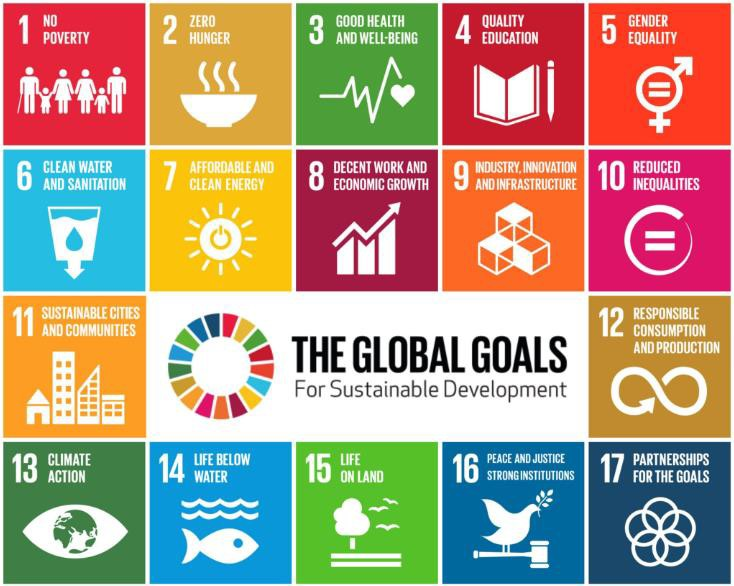

Question 3: UN SDG Awareness and Activity

Interviewees were asked if they were aware of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), and if so, whether their firm was addressing them, and in which ways they did so. All the interviewees were aware of the UN SDGs, with all but one addressing them (or planning to) to varying degrees and in various ways.

Highlights:

There is a continuum of engagement on the UN SDGs, from no impact to high-impact, as set out in the table below.

|

Continuum of UN SDG Engagement |

|||||

| No Activity

on the SDGs |

Educate Staff,

Assess Alignment on the SDGs |

SDGs Inform

CSR Strategy and Report |

External

Engagement on the SDGs (Customers, Sectors) |

SDGs Inform

Corporate Strategy |

SDGs Inform

Corporate Purpose and Business Model |

Detailed Responses:

The following is a summary of the different approaches to activating on the SDGs as described by the companies.

1) Assess alignment of CSR strategy to SDGs

This was a very common method among the companies. Many have engaged in initiatives to identify the links between their CSR strategies and the SDGs and are conducting exercises to cross-reference their current approaches to the Goals. While this practice does not lead to greater investment in the SDGs, it does enable communication as pointed out by a few of the interviewees. By going through this exercise, companies can communicate to stakeholders how their existing CSR efforts are related to the SDGs.

2) Use SDGs as a lens to set priorities on CSR strategy

Using SDGs as a lens to set priorities on the CSR strategy was a second common practice. A number of companies report they used the SDGs to prioritize their CSR initiatives. One interviewee commented that “We went through a mapping exercise to identify what we can do to support the SDGs and we set internal targets that can help us achieve the global targets”. Another reported that “We are working internally to build awareness and acumen of the Goals, map our positive and negative impacts and identify opportunities and partnerships to scale-up our contributions both locally and nationally.”

The companies using the SDGs as a priority-setting lens are focusing on the Goals where they can have the greatest impact and are working to connect their CSR targets to the SDGs.

3) Use SDGs to inform corporate strategy

One company indicated it used the SDGs to inform its corporate strategy, rather than only its CSR strategy. This company’s 2030 corporate plan was designed to support the Goals.

4) Use SDGs to inform the creation of the company’s purpose

A few companies that are participating in the United Way’s Social Purpose Institute commented they have used the SDGs to develop their company’s purpose or reason for being. The United Way’s program uses the SDGs as a tool to help companies identify the top social issues they can address through their higher purpose and business model.

5) Use SDGs in CSR reporting

A number of companies incorporate the SDGs into their corporate reporting and disclosures. Through public reporting they demonstrate how their CSR efforts help advance the SDGs. One company, for example, commented that “We have incorporated a number of the SDGs into our work and will be reporting our progress each year in our Annual Accountability Report. For example, on Goal 1, we have a number of programs and partnerships focused on tackling poverty and we will report our successes, lessons learned and where we did not achieve our goals against the SDGs.”

6) Engage customers on the SDGs

One company shared an approach to engaging their customers on the SDGs. On their donations page, they developed a platform that lists the 17 SDGs and shows how the work of over 300 non-profits links to the various SDGs. Through this platform they enable their customers to donate to the SDGs by theme (e.g. no hunger).

7) Educate staff on the SDGs

A few companies mentioned they are educating staff on the importance and relevance of the SDGs, conducting internal dialogues and raising awareness of them.

8) Promote collaboration on the SDGs

Building public awareness of the SDGs and fostering multi-stakeholder action on them was another approach mentioned by a few companies. For example, two companies sponsored the SDG Business Forum in September 2018 in Toronto, bringing together cross-sectoral senior leadership to advance the SDGs in Canada. Another company sponsored “Alberta’s Together 2018 Symposium”, a multi-stakeholder event designed to facilitate dialogue and collaboration towards implementing the 2030 Goals.

9) No SDG activity

Only one company was not addressing the SDGs in any way and was not planning to. The interviewee indicated this was not a priority for the organization.

A few commented that while the SDGs have a strong orientation to developing countries, they are all relevant to Canada, and that focusing on the SDGs helps their company fit into the global conversation on social issues.

Question 4: Non-profit Partnerships

Interviewees were asked if their company directly partnered or collaborated with not-for-profit organizations (a partnership was defined as a two-party relationship between organizations that directly collaborate on common goals and projects). This question addressed why companies pursue partnerships, the criteria they use to develop or select them, what would help them have more successful partnerships, and how they think their partnering approach will change in the future, if at all. All but one of the 27 companies that answered this question are involved in partnerships with non-profits.

Highlights:

Some of the partnerships are grassroots, some are local or community-level, others are regional, provincial, national and international. Some partnerships are initiated by the company while others are initiated by the non-profit organization. Partnerships are established for a range of purposes, with some benefiting the non-profit (e.g. helping non-profits achieve their mission) and others benefiting the company (helping the company achieve its social purpose, or its social or business goals). While grants are a frequent contribution, most companies spoke to non-grant contributions, such as in-kind support, staff expertise, tailored products and services, customer access, capacity building, contracts, and connections to other partners. In one instance a company is co-locating with its community partners and in another instance a company is strategically embedding non-profits into its operations.

These practices suggest a continuum of contributions from grants to strategic integration, in which the company and non-profit partner become more and more collaborative in contributing to social goals or the company’s social purpose. There is also an evolution of their partnership from short-term one-off partnering (e.g. sponsorship) to multi-year strategic and formal partnering (e.g., joint projects and programs).

Partnership Contributions Continuum

| Level | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

| Nature of corporate contribution and level of collaboration | Grant

Employee volunteering In-kind donations Sponsorship |

Skills-based volunteering

Best practice sharing Capacity building |

Customer access

Connection to other partners |

Social procurement

Tailored, discounted or free products Joint program delivery |

Co-location

Strategic integration/ embedment |

In addition to supporting external partners, a number of companies have created their own partnerships and charities to advance their social goals, suggesting another method of achieving social outcomes in the absence of an existing non-profit.

Companies identified over a dozen different criteria for selecting non-profit partners, the most common of which are:

- Vision and values alignment

- Contribution to the company’s social goals or social purpose

- Relevance to the business

- Risk management

Other criteria include importance to stakeholders, the opportunity provided to involve the business, works on system and policy change, collaborates with others, and helps the company distribute its social products. One company commented it had a criterion that the company itself had the capacity to contribute to the partnership, recognizing that strategic and impactful partnerships take time and energy. A few mentioned that they only partner with registered charities.

The top reason companies are partnering with non-profits is employee-related, from offering professional development to employees, to increasing employee engagement, attraction and retention. The second top benefit is to enhance the company’s reputation and brand. Two companies had unique interpretations of this rationale. One was that by elevating its brand it could attract more aligned partners, while another commented that they intentionally were not using their partnerships to build their brand and reputation as this would undermine the authenticity of their purpose.

Other benefits of partnering include learning diverse perspectives and gaining insights; increasing sales and attracting and retaining customers; advancing the company’s social purpose (as they are unable to achieve their social purpose on their own); and fostering innovation. A few companies identified traditional reasons for partnering as “the right thing to do”, and “for the purposes of giving back to the community”.

Asked what type of support or help they could use to improve the success of their partnerships, most said they needed more time, energy, capacity and resources. This was because strategic and impactful partnering requires more time than traditional grant distribution. One company commented they would like non-profits to build their capacity in partnering with business, and another commented they would like more companies to approach partnerships with a collaborative, rather than a competitive, or marketing mindset.

All but a few companies expect their partnering approach to change in five years’ time. Most expect their partnering will be more strategic and proactive, with longer term partnerships addressing systemic issues. Relatedly, companies expect they will scale up their partnerships, expand geographically, and increase their internal capacity to partner. The companies that are refining their social purpose expect to be tackling their social purpose through new social purpose-aligned partnerships. One company expects its partnering activities to be more evidence-based, leveraging the data it is collecting to make decisions on priorities. Some companies are looking to collaborate with other companies, including business customers or competitors. However, it was pointed out that companies looking for marketing benefits from their investments may not want to join a collaborative effort in which their brand profile will be lessened. A few companies anticipate they will be partnering more with governments in the future. One commented that companies need to develop a “modern relationship” with government, so they can address national social issues together. Another company expects it will be partnering with more start-ups such as social enterprises that have a double mission, producing socio-economic benefits.

Detailed Findings:

Purpose, goals and contributions

Companies were asked to describe a current partnership and the purpose or goals of the partnership. Across the different organizations, the following are the main goals of partnerships:

- Help non-profits achieve their mission

- Contribute to system change

- Achieve greater impact through collaboration

- Help the company

- Achieves its social goals

- Achieve its social purpose

- Achieve its business goals

- Address the social issues in its operations

- Sell its social products

- Provide value to customers

Companies also shared the nature of their contribution to the partnership. These are the types of contributions they provide:

- Grants (most frequently mentioned)

- Sponsorships

- In-kind support

- Cause marketing (donations tied to products)

- Employee volunteers

- Skills-based volunteering including expertise, board service, help with board recruitment, communications support

- Tailored, discounted, or free services or products

- Access to customers

- Funding for applied research

- Share best practices

- Strategic support and capacity building

- Contracts via social procurement

- Connections to other partners

- Co-location to foster more collaboration

- Joint program delivery

- Strategic integration and embedment (in which the non-profit becomes embedded in the company’s operations)

Notably a number of companies have themselves created partnerships and charities to advance their social goals.

Criteria

The following is a list of the criteria companies use to select their non-profit partners. The most common criteria are: 1) vision and values alignment; 2) contribution to the company’s social goals; 3) relevance to the business; and 4) risk management.

- Vision and values alignment:

- “We partner through shared values, mission and vision for the purpose of creating sustained change. We conduct social analysis to identify the partners we require to achieve the change and then reach out to them”

- Contribute to the company’s social goals, fits with the company’s CSR goals, helps achieve the UN SDGs

- Relevance to the company’s business, including its sector and business as a whole

- “We identified sectors that were pertinent to our business and approached non- profits in those areas”

- Risk management; robust due diligence process to ensure partnerships do not pose undue risks, e.g.:

- Non-discrimination policy, anti-bribery and corruption alignment

- Length of operations

- Credible, good reputation, not controversial

- Financial health of the non-profit

- Good governance and clear goals

- Importance to key stakeholders, including customers, employees and investors

- Provides opportunity to involve the business, including via employee engagement and volunteering

- “We partner if there is an opportunity to get involved instead of just writing cheques”

- Contributes to the company’s social purpose; has the same purpose as the company

- Collaborates with others on shared goals

- Works on system change; provides opportunities to advance policy change

- Can help the company distribute its social products to customers

- Has potential for impact, particularly lasting impact

- Helps the company address its negative CSR impacts

- Size and reach of the non-profit

- Company has the capacity to contribute to the partnership

A number also mentioned that a criterion is that the partner be a registered charity.

Benefits of Partnering

Interviewees were asked why their company chooses to partner with non-profits, and the subsequent benefits to the company from partnering. The top reason for partnering mentioned by about one-third of the interviewees is employee-related, specifically employee professional development, engagement, attraction and retention. The second top reason was brand and reputation, including the ability to gain buy-in from stakeholders. The third most frequently mentioned benefit is learning from the partner and partnership.

- Improves employee experience

- Provides professional development opportunities for staff; staff education; strengthens employee skills and insights

- Employee engagement and fulfillment

- Employee attraction; access to talent; ability to find talent

- “When we organize our philanthropic events, we always invite students to come. Some of the superstars we have come across will join our philanthropy project for days for a chance to work with us in our offices and test the culture, and we get to see how they conduct themselves and decide whether we might want to hire them.”

- Employee retention

- Builds brand and reputation, positions the company as a leader, builds its exposure and visibility

- “Helps us get buy-in from stakeholders” A unique brand benefit mentioned by one company is that by elevating the company’s brand, recognition and awareness, it was able to attract other partners interested in similar objectives. Another company mentioned that they explicitly do not seek marketing benefits from their partnerships, because it was not pursuing partnerships for brand and reputation purposes. Instead, it was pursuing partnerships to help it achieve its social purpose. This same company also commented that it was not effectively communicating its work and impacts, pointing to a distinction between marketing and communications.

- Gains insights and learns from the partner; partnerships help contribute new perspectives; opportunity to leverage partner expertise and tap into their insights and perspectives

- “It goes back to valuing diversity and perspectives. We find that some of the partners we work with have really helped shape our thinking”

- “Because they know the landscape. We know what we know about social issues from listening to and learning from people with lived experience and the organizations that support them and advocate on their behalf”

- “We acknowledge our expertise is not in social impact/serving our communities, so we need to work with them to have the impacts we want”

- Increases sales; helps attract and retain customers; helps connect to customers

- “Having partnerships is a unique way to communicate with the customer”

- “Our highest performing business units are all involved in the community; we believe growth depends on our connections in the community”

- Advances the company’s social purpose

- “Our goal is to grow social benefit and we cannot do that alone, so that is why we partner”

- “How couldn’t we? We can’t do everything by ourselves. We are dependent on so many organizations as they support our social purpose alignment”

- Contributes to their social goals

- “We partner to make an impact on some of the most pressing issues affecting Canada”

- Generates innovation; collaborates with partners on research and development on business and social innovation

One company commented that many years ago it contributed to non-profits in the community because at the time it was trying to build a community for its employees to support its operations in frontier areas. Now that developing new communities is no longer its focus, it has other priorities.

A very small number spoke to traditional reasons for partnering as being the right thing to do and a chance to give back to the community. One company mentioned that partnering was part of its DNA.

One company commented that they do not look at their partnerships as a marketing opportunity.

Support for Successful Partnerships

Companies were asked to describe what would help their firm have more successful partnerships. Interviewees identified a range of needs, some of which are likely unique and others which are shared between organizations. The top need was for more time, energy, capacity and resources. A few also mentioned they could benefit with assistance identifying relevant partners. One company would like assistance provided to non-profits to help them have more effective partnerships with the private sector. Another company commented on the need to have more pre-competitive partnerships with industry peers, but most peers are focused on realizing marketing benefits from their partnerships which hinders collaboration.

These are the identified needs to enhance corporate-community partnering:

- More time, energy, resources

- “We think of it as a spectrum of who we can partner with, from a support role to a transformational role. If we had more people on the team, we could go deeper into some of these partnerships.”

- Assistance identifying relevant and values-aligned partners, such as a data-base or match-making service

- Help for non-profits to learn how to collaborate with the private sector; help them learn how to participate in strategic partnerships with the private sector

- “Many non-profits are having issues transitioning from pure philanthropy to strategic partnerships. Many of them don’t understand how to do that. In order for a partnership to be successful, it can’t just be us writing a cheque. They need to show us that they’re effectively making use of the money.”

- More companies seeking to partner in a pre-competitive space, rather than companies who are only focused on marketing objectives in their partnerships

- More clarity on priorities

- “We need to determine what do we want to do and who is best to partner with”

- “We need increased strategic alignment to our corporate social purpose”

- More support from executive leadership

- Demonstrate value-added of community relations

- “We need to show even more how our community relations could add value to our business. The more value we can create for business, the more we can justify the community value, and vice versa”

- More time communicating what the company does; a better job communicating about its partnerships

- “We haven’t spent a lot of time communicating what we do. We’d like to focus more on telling the story of the work we are doing in an authentic way without doing any PR marketing. We want to raise awareness to support those organizations with communications. We are in the background and people don’t actually know what we’re doing”

Anticipated Changes to Partnering in Five Years

Companies were asked to identify how their partnering approach will change in five years if at all. The most common anticipated change is that companies will become more strategic and proactive with longer-term partnerships addressing systemic issues; the second most common shift is that companies will scale up, expand geographically, and increase their internal capacity to partner.

The companies identified the following potential changes to their partnering approach in the next five years:

- More strategic, proactive and formal; tied to a community strategy or social purpose; more long-term approach and long-term partnerships; address big, systemic issues

- “It needs to become more formalized. Our CSR committee has been taking steps to be a bit more intentional going forward with setting clear objectives and a clear vision for partnerships”

- “I think right now organizations come to us for funds and propose ideas. As we learn more, we will be in a position to go to partners with ideas and build initiatives based on what we learn”

- “Proactively pursue partnerships rather than just react”

- “We would like to see ourselves get more involved in multi-year projects that have more impact. We would like to be involved in partnerships over a five-year time frame”

- Scale up, build internal capacity, do bigger things, expand geographically

- “Scaling-up our partnerships five times”

- “Increase capacity to have more partnerships”

- “Expand our partnering approach to achieve more impact through more partnerships across communities, the province, and Canada”

- “Pursue national partnerships”

- Launch an employee volunteering program

- “We’ll be able to leverage our highly talented employees to contribute to the non-profit sector”

- Leverage data and become evidence-based

- “We will collect more data and decide what we are going to do based on the data”

- Collaborate with business customers and industry peers

- “We may start partnering with others within the industries in which we operate to advance our industry. We see that if we want to move a social issue forward, it will take more than just one non-profit or company. Right now, people are hesitant because they may get fewer perceived benefits, such as branding it as “your partnership or program”. It’s beginning to shift though”

- Collaborate with government; engage at a policy level

- “We need to develop a modern relationship between companies and government”

- Partner with more start-ups that produce economic and social benefits and have a double mission

- More alignment to the SDGs

- Measure the company’s social impact

A very small number commented that they didn’t expect any shifts in the partnering approach in the next five years.

Question 5: Partnership Challenges

Companies were asked to identify the major challenges they face when partnering with non-profits. They identified about a dozen challenges that limit their success.

Highlights

Companies were diverse in the challenges they identified, likely a function of where they are in the partnership journey.

Top challenges include:

- Cultural differences between the private and non-profit sectors

- Demand exceeds supply

- Lack impact measurement

- Lack information on non-profits

Other challenges include:

- Not knowing how to have the biggest impact

- Values misalignment

- Different challenges working with small versus large non-profits

- Challenges working in rural, northern and Indigenous communities

- Duplication in the non-profit sector

A final challenge identified by a few, which seem to point to future issues as companies seek to scale up deeper collaborations with non-profit organizations, is how much of civil society distrusts business, and are limited in its understanding of how and why to partner with business on common goals.

Detailed Findings:

Cultural Differences: A top challenge of partnerships is the different expectations and mandates of the private and non-profit sectors. The two sectors operate differently, with different cultures and mindsets. Non-profits find it challenging to understand the business context and they lack a customer support and service capacity. Often non-profits are nimbler than companies.

Number of Requests: A number of companies commented that they get so many requests that their biggest challenge is trying to focus on areas where they can make the biggest impact with their funding and time. Companies find that the demand far outweighs their capacity.

Impact Measurement: A number of companies identified impact measurement as a partnering challenge. As one of the companies said, “We need tools to measure impact”. Small non-profits particularly lack the tools or resources to measure their impact. Companies need to determine where they could make a difference and how to measure the difference. Lack of impact measurement makes partner selection difficult. Without impact measurement it is difficult to demonstrate value and return on investment.

Lack of Information: A lack of information and data on non-profits in Canada is a common barrier for a number of interviewees. Publicly available information, including assessments and measurement would help with the selection process. Companies find it challenging to evaluate the reputation or track record of a non-profit, and the lack of a provincial directory of organizations compounds this problem.

How to Have the Biggest Impact: Lack of knowledge of how to make big impacts is an additional issue for some companies. Companies that want to make a positive impact find it difficult to determine the process of how to do so. Some partnering strategies could be more impactful than others, but how do companies know which are best? Finding the right partnership fit is challenging and knowing how to have a meaningful impact is not easy. Related to this issue, they have problems knowing what their priorities should be, including being able to navigate through all of the opportunities.

Small Non-Profits: Companies discussed the challenges they face partnering with small or large non-profits. They find that small non-profits are innovative, agile, flexible and nimble. With smaller organizations, partnerships can have more impact and investments can go further. However, small non-profits need training, coaching and capacity building as they lack sophistication. They are resource-strapped and lack core funding. “Sometimes it is difficult to even find the time to sit down and do strategic planning with small organizations. It is easier to just give them money and supplies [than partner in a meaningful way].” One company wanted its partner to scale up and provide regional services, but it was going to be very cost-prohibitive to deal with them. The non-profit lacked the internal capacity to meet the broader needs of the company.

National companies especially identify a challenge partnering with smaller non-profits. According to one, “We can’t be in every city or town.” National non-profits tend to be in Toronto and some companies seek to allocate their funding across the country in terms of population and business. Relatedly, another company commented that “When we have no presence in a community, we lack an understanding of their priorities and effectiveness.”

Large Non-Profits: On the other hand, larger non-profits tend to have good reporting, accountability, resources, capacity, reach, and business knowledge for partnering. They understand the complexity of multi-province and territory issues and geographic challenges. Despite this, companies find that large non-profits can be conventional, overly bureaucratic, less flexible, and slow. “By partnering with large organizations (as a national company) we missout on small innovating non-profits.” While they may be more sophisticated, the dollar may not go as far. “They are sometimes more heavily resourced than we are, but they aren’t thinking as innovatively or creatively as we’re thinking.”

Urban Versus Rural Non-Profits: Companies identify challenges working across the spectrum of urban, rural, northern and Indigenous communities. They find it difficult implementing consistent strategies within all settings and provinces. They find specific challenges working with remote and rural Indigenous organizations and communities, as they have very different cultures and partnering with them requires more time and resources.

Duplication: A few companies identified duplication in the non-profit sector as a challenge they faced. They find multiple non-profits trying to tackle similar issues who are not working together or partnering. Companies can receive five different applications for organizations doing similar work and wish the non-profits could merge their operations. Some companies try to encourage partnering but have found it difficult: “We try to partner them together, but there are constant conflicts or minor disagreements.”

Values Misalignment: Another challenge identified by a few is that there can be unaligned values and a lack of a mutual benefit. There can be misalignment on goals and objectives when making joint decisions, which can be a source of friction.

Some other challenges include:

- Not enough face-time with partners

- Employee turnover at non-profits make it challenging to establish a long-term relationship

- Business cycles make it difficult to be consistent and long-term

- Policy of not funding more than 15% of a charity’s annual revenues (so they are not reliant on one source of funding) can be a limiting factor

- Challenge in motivating other businesses to become involved in the partnership

- Non-profits who do not operate as registered charities cannot become partners due to company policy

One final challenge suggests where future difficulties might lie as companies advance along the partnership path: non-profits being held back by old mindsets and assumptions of the role of business as community partners. These mindsets are revealed in the following comments:

- “One challenge is the fact that there is a large distrust of business within the charitable sector and civil society. They like receiving a cheque but are skeptical of the broader partnership concept which is new to many.”

- “We want our partners to think of us as allies or partners, but they continue to see us as a charitable funder.”

Question 6: CSR Implementation Barriers

Interviewees were asked to list the barriers to implementing CSR at their firm and suggest strategies to overcome them. A number of respondents commented that they did not face any barriers, and many spoke to having internal support for CSR at the leadership level and throughout the organization.

Highlights:

Of all the barriers identified, internal barriers are by far the most common. Four top barriers named by respondents include:

- Lack of buy-in from senior management and executive leadership

- Lack of evidence of the CSR business case

- Lack of time and resources

- Difficulty in shifting the corporate culture to embed CSR principles

These barriers are interlinked and relate to challenges in understanding the business benefits and the role of business in social change. In fact, the most common solution is to develop the CSR business case to get senior management on board.

Interviewees identified a number of roles for the Federal Government to help address the barriers. They include mandating CSR reporting, making CSR a government priority, fostering regulatory harmonization and experimentation (e.g. via regulatory sandboxes6), adopting policies that require companies to address CSR issues, penalizing those that fail to do so, and providing financial incentives for achieving CSR targets.

Some of the responses demonstrate the challenges of being on the CSR frontier:

- Trying to get a company to shift its mindset from a giving culture to a social innovation culture

- Challenge of regulations that limit social innovation and experimentation

- The inadequacies of incremental solutions to address societal challenges and the need for government to play a stronger role influencing corporate behaviour on CSR

- The need to change the paradigm of business from a focus on profits to a focus on contributing to society through its core business

As one interviewee summed it up: “Is society here for business or is business here for society? We need to better understand the role of business in society.”

Detailed Findings:

Responses to the question on the barriers to advancing CSR and measures to overcome them are summarized in the table below.

Barriers to Advancing CSR

| Type of Barrier | Barrier | How to Overcome the Barrier |

| Internal Issues | Lack of buy-in from senior management /

executive leadership

“Obtaining senior management buy-in is the most challenging barrier to implementing CSR.”

“To be an influencer with executives, I need to be able to identify CSR as an opportunity and to demonstrate how CSR can help manage an identified risk for the company.” |

Develop the business case and identify the

return on investment, such as the brand- building benefits of CSR, the business risks that CSR can address, and the opportunities that CSR opens up for the firm.

Demonstrate how CSR can support the corporate strategy.

Change the paradigm of business, from one of making profits to one where business contributes to society through its core business and reason for being. |

| Lack of evidence of the CSR business case

and return on investment

“We lack data to demonstrate the business case for adopting CSR.”

“The belief that engaging in CSR is too costly and the need to demonstrate it can actually be cost effective and make money (e.g., positive branding). The worry that it will result in lost revenue even though current markets are moving towards CSR initiatives.” |

Provide evidence of the business case.

Invest in CSR measures that both benefit society and generate profits for the company, where there is a win-win.

“Some companies like Unilever have been doing CSR for so long they have data that proves that CSR and sustainability have actually improved their company.” |

|

| Gaining organizational buy-in to integrate

and embed CSR; change management and organizational culture are challenging

“Change management issues are a challenge. Changing requires effort to get everyone on board. To make everyone try something new is difficult.”

“We are doing things differently and adjustment is necessary. These changes involve risk and effort, and just getting the bandwidth from various colleagues to try something new is difficult.” |

Get senior management to buy-in and

become champions. Frame CSR so it resonates with senior management.

Put CSR in the business strategy and connect it to individual performance goals and objectives.

Use change management techniques; provide internal coaching.

“Create the understanding organizationally that this needs to be worked on across the organization, it’s not one employee’s job. As organizations mature in their CSR journey, the idea tends to take hold.” |

| Type of Barrier | Barrier | How to Overcome the Barrier |

| “Our internal culture revolves around the

fact that we are a business and because of that there is a lot of doubt as to whether we should even participate in this space.”

“In practical terms there are barriers everywhere in a company. The right behaviour and ways of doing things require a cultural transformation and adaptation.” |

“Make CSR part of the corporate culture and business processes and implement it across the board.”

“Transparency, reporting and tracking progress helps with change management.” |

|

| Lack of time and resources

“We have limited bandwidth within the organization, and it requires a new kind of skillset.”

“We have limited financial and human resources and we have to be careful not to dilute our impact by heading off in different directions.”

“Every company I’ve ever worked with, almost nobody has extra time. It’s really hard to get people engaged, because they are already stretched – it isn’t because they don’t care, but because they’re stretched.” |

Provide evidence of the business case.

“Overcome the “old way of thinking”, for example thinking that engaging in CSR would be an additional activity to the daily workload, instead of focussing on integrating CSR into all activities.” |

|

| Priority-setting in face of so many

opportunities

“The other big challenge is getting on top of opportunities. There are literally hundreds of opportunities that emerge in a given month.” |

None identified. | |

| Shifting the mind-set from charitable giving

to social innovation

“Our barrier is that we’re so rooted in the concept of giving, but the shift is trying to change to how we think about societal issues less from a giving perspective, and more on an innovation level. That’s the mindset we’re looking to make, and the cultural shift takes time.” |

None identified. |

| Type of Barrier | Barrier | How to Overcome the Barrier |

| Departmental silos

It is difficult to get departments to work together on CSR. |

None identified. | |

| Communications | Difficulty communicating CSR internally and

externally |

None identified. |

| Industry Issues | Lack of consistency in the industry, lack of a

level playing field |

Government leadership. |

| Regulatory issues constrain CSR

Lack of regulatory harmonization across jurisdictions.

“Our barrier is finding ways in heavily regulated environments to do some of the experimental work to really implement CSR.” |

Consistent regulations across jurisdictions. Engage the regulators to seek changes.

Encourage regulatory experimentation for CSR outcomes. |

|

| Customer

Demand |

Inadequate customer demand for

sustainable products

“We are trying to accelerate sales of products with highest sustainability value. The company is constantly challenged by customer demand for cheaper products and not the sustainable products.” |

None identified. |

| Societal

Challenges |

Lack of scale and synergy to address big

societal challenges |

Identify top issues to address through government and business collaboration and effective government policies. |

Non-profit Challenges

Three challenges working with non-profits were identified:

- Difficulty narrowing down the number of non-profits to work with

- Competition between non-profits negatively affects collaboration

- “Non-profits can’t collaborate. They have similar long-term goals but disagree on the approach”

- High turnover of non-profit staff

The recommended solutions for these non-profit challenges include being strategic, focusing and streamlining efforts, and aiming for long-term partnerships.

Federal Government Roles to Address Barriers

A number of Federal Government roles were identified to address the barriers and help business advance on CSR, including:

1) Provide financial incentives – companies that set bold CSR targets should receive compensation for achieving them;

2) Mandate CSR reporting so that CSR practices can be compared across companies and more data becomes available to develop the CSR business case;

3) Support a multi-sectoral partnership approach to complex social issues so that businesses become engaged;

4) Make CSR a government priority, so that more companies include CSR in their corporate strategies;

5) Foster regulatory harmonization across provinces and encourage regulatory experimentation for CSR outcomes; and

6) Adopt policies that encourage companies to address CSR issues and penalize those that don’t.

Question 7: Role of Intermediaries

Interviewees were asked to identify if intermediaries played a role in their partnerships with non-profit organizations and if so, to describe the role. They were given examples of organizations such as incubators and accelerators that offer collaborative working spaces, learning platforms and social innovation assistance. Most described their approach as engaging with intermediaries for help executing their CSR priorities. A few were too early in their CSR strategy to have identified a role for intermediaries, and a small number preferred a direct hands-on approach to partnering over intermediaries.

Highlights:

It appears that most of the respondents are not engaging intermediaries for help in partnering with non-profits. They are primarily leveraging them to advance their social innovation goals. Some companies act as intermediaries themselves, some leverage their partnerships as intermediaries, some partner with their intermediaries, others fund intermediaries and others mention that the multi-stakeholder collaborations they are involved in function as innovation incubators.

Interviewees point to a range of uses and services they receive from intermediaries, from innovation space and assistance (such as pitches, pilots and live demonstrations), to industry collaboration on solutions, to traditional services such as facilitation, expertise, policy, advocacy, measurement, standards, information, research, audit and evaluation, grant-making and community brokering.

Companies appear to be experimenting with different roles and partnering models to advance social innovation and impact in their communities. Some are focused on addressing social issues while others are focused on improvements to the business model in ways that will benefit society.

A few respondents named an intermediary partner. The post-secondary sector and the United Way’s Social Purpose Institute were most commonly referenced.

Detailed Findings:

The interviews explored the role of intermediaries, accelerators and incubators in helping companies execute their CSR priorities. About two-thirds responded positively that they benefit from these services. Some were too early in their CSR strategy to have identified an intermediary role, some prefer a direct hands-on approach to partnering and collaborating, and one believes intermediaries do not play a significant CSR role in Canada.

Most use intermediaries for help with CSR generally, not necessarily for assistance in developing partnerships with the non-profit sector.

Types of Intermediaries

For those who named an intermediary partner, most common were post-secondary institutions and the United Way’s Social Purpose Institute. Other examples include MaRS Discovery District7, UN Global Compact Canada, Imagine Canada8, LBG Canada9, Rally Assets10, Habitat for Humanity11 and Provincial Government ministries (health and social development).

Different Approaches

Interviewees provided insight into different ways they work with intermediaries, incubators and accelerators, revealing a diversity of models and engagement strategies to foster connections and innovation. The different approaches include:

- Incubators and accelerators as partners

- “We engage with intermediaries in hosting incubator or accelerator and innovation sessions; we pitch innovations from our business to their members”

- Partners as incubators / accelerators

- “We use our partners also as our incubators because they have a lot of information that we don’t have access to”

- Act as intermediaries and innovators themselves

- “We consider ourselves playing more of an intermediary role than our partners”

- “We have our own in-house innovation team”

- “We set up community boards where we operate to provide advice on our granting strategies, and they connect us to local non-profits”

- Funding intermediaries

- Participating in social innovation collaborations which function like incubators

- “We benefit from being part of collaborative efforts, which can be almost like incubators”

Different Uses

Across the interviews, it appears that companies are tapping into intermediaries, incubators and accelerators for a range of uses. They use these services to access the following (not listed in order of priority):

- Incubator space / co-location facilities to foster innovation and cross-pollination

- Innovation assistance (e.g. pitches, pilots, live demonstrations)

- Industry resources, networks and collaborations; sector CSR programs and resources

- Facilitation skillsets, credibility, neutral convenor

8 http://www.imaginecanada.ca/

- Policy and advocacy work, government policymakers

- Standards, benchmarks and measurement methodologies

- Information, research and data analytics

- Audit and evaluation assistance

- CSR best practices, expertise and subject matter experts, help developing a social purpose

- Asset brokerage services (e.g. surplus goods management)

- Workforce training and hard-to-employ employees

- Granting services

- Community partners

Question 8: Federal Government’s CSR Role

Interviewees were asked to consider the role of the Federal Government in supporting, accelerating and scaling CSR in Canada. They were given eight possible responses, and offered the opportunity to suggest other roles, including no role.

Notably, there was unanimous agreement among all interviewees that the government should play a role to advance CSR.

Highlights:

The two main opportunities for the Federal Government to advance CSR supported by most interviewees include:

- Convene multi-stakeholder dialogues and collaborations: Convene and facilitate dialogue between the private and non-profit sectors on CSR issues and help build multi-sectoral partnerships with government acting as neutral arbitrator among diverse stakeholders. This approach can be used to identify and address priority SDGs, identify broad national social goals and campaign, explore the development of a national CSR strategy, and modernize CSR language and practices.

- Create incentives to encourage take-up: Provide a package of incentives to encourage CSR adoption in Canada, including financial or tax incentives, recognition programs or awards and government CSR procurement. One approach is to offer a Social Innovation Challenge or Competition on a significant CSR issue.

Other top opportunities include:

- Best Practice Resources and Benchmarks: The Federal Government could fund and disseminate best practice guidelines, standards, tools, business cases, social outcome measurement and other CSR resources to improve corporate social performance. A guide on how to develop CSR strategies and social purpose business models would be useful, along with benchmarks and industry standards, including a standard for business collaboration with non-profits.

- Social Trends and Risks Research: Conduct, provide or fund actionable research into social issues and business risks that stem from them, so that companies can address them in their business strategies. Survey companies to identify existing CSR data gaps and support research to address them, use this information to support corporate social innovation. Ensure national, provincial, research and local social trend data is available.

- CSR Procurement: The Federal Government should include CSR as a factor in procurement and encourage its suppliers to engage in CSR and foster CSR across their supply chains.

- Professional and Industry Associations: The government could provide support to professional and industry associations to help their members adopt CSR and social innovation. CSR could become a component of professional designations and educational standards and requirements. Industry associations, including chambers of commerce, are a channel to small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and can become a platform to engage SMEs on CSR with government support.

Other measures identified by responses include:

- Intermediaries: Funding intermediaries, accelerators, incubators, innovation labs and other scaling organizations to provide support for social innovation and impact.

- Disclosure and social impact metrics: Requiring large companies to disclose their CSR performance and support efforts to measure social impact to enable benchmarking.

- National strategy and scorecard: Developing a national strategy on key CSR issues, and a national scorecard on CSR.

- Board education: Engaging boards, shareholders and the investment community on CSR through CSR education and symposiums.

- Leadership: Leading by example by pursuing CSR in government operations.

- Post-secondary education: Supporting post-secondary institutions to advance CSR within academic curricula.

Detailed Findings:

Top Interests:

1) CSR Collaboration