Anthropological Newsletter, May 24, 2412

Working in the area where what used to be called the Georgia Strait intersects with the former False Creek a team of archeologists from Sri Lanka have finally found the mysterious island that was eventually called Mylikah (Queen of Islands), known in those times as Granville Island. Because of the unique adjustments it made during the 21st century Mylikah became known as a centre for the transformation of shoreline environments worldwide and the heart of the evolution of the Salmon Nation, the name that the watershed that stretched down the length of the Pacific coast was called. Salmon Nation itself became an exemplar of what is now referred to as the Great Awakening that took place beginning in the year 2026 and lasting for over 100 years. There it was 6 metres underwater, but still well preserved by the silt in which it was submerged and because of the advance design of the buildings of the early to mid 21st Century on the Island.

Islands and water are inseparable. The sea and the strand define one another, their relationship always changing over time. The marshy shoreline environment in and around Granville Island and the waters of False Creek have undergone profound changes over the past 150 years. And many hundreds of years ago a similar island community in the Nile delta called Heracleion underwent profound changes, as well.

Vancouver’s Granville Island was once a sandbar and an Indigenous fish trapping site. False Creek was lined by old-growth forests and fed by salmon streams. The area was rich in fish, clams, mussels, grasses, berries and waterfowl making for a varied and easily accessible menu. The Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) nation’s Sen̓áḵw village was located nearby underneath what is now the Burrard Bridge and behind the former Molson Brewery and up to seven Indigenous nations shared in the harvest.

During the latter part of the 19th century European settlers poured into Vancouver. The bounty and abundance of the west coast in those days evoked an industrious and energetic response on their part, marred by greed, avarice and short-sightedness. The settlers logged the magnificent forest in their immediate environment and Stamp’s Mill, renamed Hasting Mill obtained a lease for over 40% of the land that is now the downtown. By 1886 False Creek had two substantial lumber mills, a wood planing operation, a lime kiln and a brickyard. Most of the development was taking place at the eastern end of the Creek in the vicinity of the foot of Main Street. In less than three decades, the days of False Creek as a quiet inland waterway with wetlands flanked by dense forest was gone. In 1913, the Squamish people on the south shore were set adrift in a barge and Sen̓áḵw village was burned to the ground.

Granville Island in its present thirty-four acre form was created in 1916 with mud from dredging operations held in place by a crib. Leases were let in early 1917 and by 1923 all of its industrial lots were taken. By late 1918 the tidal flats east of Main were filled in and had become the site of the CPR and Great Northern Railway stations, freight yards and rail yards. Granville Island, then known as Industrial Island, employed 1,200 workers and was home to a wide range of industrial manufacturers. They made wire and fiber ropes for logging, chains for pulling barges, and other materials for the shipping, mining and logging industries. Barges brought in lumber from up the coast and took away chains and other supplies.

Granville Island in its present thirty-four acre form was created in 1916 with mud from dredging operations held in place by a crib. Leases were let in early 1917 and by 1923 all of its industrial lots were taken. By late 1918 the tidal flats east of Main were filled in and had become the site of the CPR and Great Northern Railway stations, freight yards and rail yards. Granville Island, then known as Industrial Island, employed 1,200 workers and was home to a wide range of industrial manufacturers. They made wire and fiber ropes for logging, chains for pulling barges, and other materials for the shipping, mining and logging industries. Barges brought in lumber from up the coast and took away chains and other supplies.

By the late 1920’s the False Creek basin was in trouble. Raw sewage emptied into waters of the Creek. The northern shoreline was littered with dilapidated wharves, abandoned boat hulls and trestles. The water quality was further compromised by dumping ash, manure and rusty old cars in it. Emissions from eleven sawmills and BC Electric’s expanding gas works polluted the air. Politicians of that era began to refer to it as a “filthy ditch” and some lobbied to have it filled in. There was little to suggest a renaissance was in the cards.

However, in the 1970s, Granville Island and False Creek were transformed into a busy, mixed-use waterfront area that is highly valued by residents and visitors alike. In addition, False Creek is also home to critical infrastructure that many Vancouverites rely on, including water, wastewater, electrical, communications and transportation systems. These are spread throughout the False Creek floodplain area and include the False Creek Energy Centre which provides heat to the Olympic Village area and a growing number of condos and buildings used for business and government in the False Creek Flats area. Major SkyTrain stations and sections of both the Canada Line and Expo Line, and transportation arteries, including roads, bridges, bike paths, and the False Creek Seawall also surf the crust of the floodplain.

Finally, with everything else going on in the area, in 2002, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) finding that they could reclaim the area of their traditional village Sen̓áḵw, beside Granville Island. The land was handed back to the nation and is now the site of a housing development led by a partnership between the Squamish Nation, Nch’ḵay̓ Development Corporation (the Squamish Nation’s economic development arm), and Westbank — under the partnership name Nch’ḵay̓ West.

“Floodplain” is the operative word here. In the context of the temperature rise associated with global warming, the whole area is susceptible to flooding over the next 20-30 years by increasingly aggressive king tides and, from below, by a rising water table. Here is where Heracleion is an instructive example. Though it was referred to in ancient texts, for many centuries it seemed that Heracleion had vanished and become barely more than a legend.

Then, in 2000, after searching in the vast area of the Abu Qir Bay off the coast of Egypt, French archaeologist Franck Goddio and his team saw a colossal face emerge from the watery shadows. Goddio had finally encountered Heracleion, completely submerged 6.5 kilometres off Alexandria’s coast. The ruins and artifacts made from granite and diorite are remarkably preserved, and give a glimpse into what was, 2300 years ago, one of the great port cities of the world. Built around its grand temple, the city was criss-crossed with a network of canals, a kind of ancient Egyptian Venice, and its islands were home to small sanctuaries and homes. Once a grand city, its history had been largely obscured and slipped quietly under the sea – https://www.thetravel.com/the-lost-city-of-heracleion-or-thonis/.

Then, in 2000, after searching in the vast area of the Abu Qir Bay off the coast of Egypt, French archaeologist Franck Goddio and his team saw a colossal face emerge from the watery shadows. Goddio had finally encountered Heracleion, completely submerged 6.5 kilometres off Alexandria’s coast. The ruins and artifacts made from granite and diorite are remarkably preserved, and give a glimpse into what was, 2300 years ago, one of the great port cities of the world. Built around its grand temple, the city was criss-crossed with a network of canals, a kind of ancient Egyptian Venice, and its islands were home to small sanctuaries and homes. Once a grand city, its history had been largely obscured and slipped quietly under the sea – https://www.thetravel.com/the-lost-city-of-heracleion-or-thonis/.

Over time, Heracleion was weakened by a combination of earthquakes, tsunamis, and rising sea levels. At the end of the second century BCE, probably after a severe flood, the ground on which the central island of Heracleion was built succumbed to soil liquefaction. Earthquakes can also cause liquefaction, and earth tremors and tidal waves were reported by ancient historians during the time of Heracleion’s submersion. The soil around the south-eastern basin of the Mediterranean is prone to liquefaction. This fact plus all of the surrounding aspects of the situation resulted in the city virtually sliding into the sea.

Knowing that Granville Island is composed of sand and sludge dredged up from the False Creek basin, it is not hard to imagine a similar fate for Granville Island. Liquefaction is most often observed in saturated, loose, low density or uncompacted, sandy soils. This is because a loose sand tends to compress when a load is applied. If the soil is saturated by water, a condition that often exists when the soil is below the water table or sea level, then water fills the gaps between soil grains, essentially turning into a kind of gooey substance that is incapable of supporting the weight of built structures.

Granville Island’s history, as well as its susceptibility to the impacts of the climate crisis make it an ideal coastal adaptation laboratory. Its Indigenous history, iconic status and accessibility to the public also make Granville Island an ideal site for a unique response to the climate crisis.

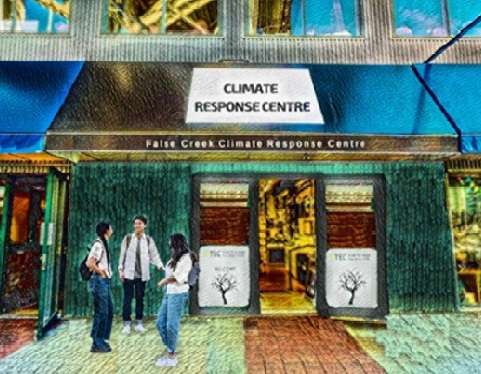

The False Creek Climate Response Centre will be a unique institution designed to respond to the systemic, social, and cultural dimensions of climate change in shoreline environments emphasizing the historic wisdom of Canada’s Indigenous peoples. The Centre is a joint project of Green Technology Education Centre (GTEC) False Creek Friends Society. (FCFS) and Persephone Brewing Company.

The False Creek Climate Response Centre will be a unique institution designed to respond to the systemic, social, and cultural dimensions of climate change in shoreline environments emphasizing the historic wisdom of Canada’s Indigenous peoples. The Centre is a joint project of Green Technology Education Centre (GTEC) False Creek Friends Society. (FCFS) and Persephone Brewing Company.

The Climate Response Centre will train and educate the community about coastal adaptation in particular and climate change in general. Indigenous reconciliation will be supported by hosting Indigenous led programs and events. The Centre will also provide support services that build community, help it face the widening impacts of climate change, as well as offering a social environment in which arts and culture play a key role in inspiring a constructive response to climate change. Lessons learned in envisioning, developing and establishing this Centre will be documented in forms that are transferrable to other urban environments.

A scalable model for centres in towns and cities across the country, the Climate Response Centre utilizes design thinking in its development and embraces a hub and spoke model of operation that can incorporate a range of groups and organizations. As the impacts of climate change are felt more deeply, an increasing need will emerge for centres to which people can turn for information and support. The Climate Response Centre will be that and, as well, will offer opportunities to learn, engage in constructive dialogue and develop solutions. One such opportunity could be to save the heroic Granville Island once again.

In the early days of his career, Arden Henley started a street based program for at-risk youth in Vancouver, BC. He designed and implemented two treatment centres for children, youth and their families and co-founded a Family Therapy Institute. At City University, Arden initiated a Masters of Counselling degree, now the largest program of its kind in western Canada, and served as Vice President. Widely published, Arden is a speaker and leader and holds a Doctorate in Education from Simon Fraser University. Currently he is the Executive Director of the Green Technology Education Centre (GTEC).

In the early days of his career, Arden Henley started a street based program for at-risk youth in Vancouver, BC. He designed and implemented two treatment centres for children, youth and their families and co-founded a Family Therapy Institute. At City University, Arden initiated a Masters of Counselling degree, now the largest program of its kind in western Canada, and served as Vice President. Widely published, Arden is a speaker and leader and holds a Doctorate in Education from Simon Fraser University. Currently he is the Executive Director of the Green Technology Education Centre (GTEC).