Listen to the author reading this article (11:40)

Fire has always fascinated me. Throughout my childhood, my father was the warden of a Boy Scout Association campsite in Worcestershire, England. Every weekend, he took my brother and me to that campsite in a small patch of mixed woodland: oak, beech, horse chestnut, silver birch, and elm. We loved to collect fallen branches and build dens. Then, in the evenings, as the day faded into darkness, we would build and light a fire around which to sit with friends and tell stories. This was my favourite time. I loved the magical mixture of darkness and light. The flickering flames of the fire held the dark wood around us and its inhabitants at bay. The Fire provided warmth, comfort, and safety. Fire was Home.

Half a century later, half the world seems to be on fire. Friends in Canada and the U.S. talk of smoke filled skies, air too ash-full to breathe. The news is full of bewildered holiday-makers standing on Greek beaches, fleeing hotels consumed by forest fires. Even here on the cold, damp Welsh borders, plagued more by flooding than fires, we remember last summer when temperatures soared to record highs, leaves fell early from scorched trees and farmers prayed for rain. There’s a growing awareness that things are out of balance, that we are entering a time of extremes. The sun, that big old ball of fire in the sky that gives us all life, no longer seems like the welcome friend that returns each summer to warm our aching winter bones, ripen our crops, and top up our vitamin D. We have allowed a situation to develop where the old friend is showing up very differently – less warm embrace, more flaming sword. The ancient god in his vengeful aspect. Fire no longer feels like Home.

Forest fire in British Columbia, Canada

My positive childhood experiences established in me a foundational relationship with Fire as a place of comfort and safety. But I also knew that Fire could hurt me and had to be handled with care and respect. I had held on to matches a little too long, burned my fingers, felt Fire’s bite. My father and various other adults had drilled into us the importance of not leaving a fire untended, of making sure it was properly extinguished before we walked away. One memory in particular springs into my mind.

It was Christmas time. I was a boy, eight years old, maybe. My younger brother and I were sitting on logs beneath the massive fire shelter situated in the Scout Woods. We were gathered there with several other families. We had all shuffled up from the Scout Hut, wrapped in thick coats and scarves to protect us from the cold December night, excitedly chattering amongst ourselves. We had been told that we were to sit around the central fire and wait for a special visitor who was coming to see us. Who could be coming to visit children on a dark December night? The older ones amongst the children, having experienced this ritual before, smiled knowingly to themselves and watched for the first glimpse of the red suit and beard.

It was already turning out to be a cold winter that year, so it was good to feel the warmth from the central fire. The adults had built it extra large to beat the winter chill. It was undoubtedly magical, whatever your age, to sit in the darkness watching the flames licking and sparks flying up towards the smoke hole in the top of the shelter roof. The cold night air drew the fire up fiercely towards the square of star-flecked black sky.

Then a jingle of bells and crunch of footsteps behind us drew our attention. The childrens’ heads turned as one towards the sound. We peered into the darkness, waiting for our eyes to adjust after the brightness of the flames so that we might see who was coming to visit. All eyes were focused on the woods beyond the shelter. All eyes bar those of one of the youngest children who had noticed something the others had not.

“Fire!” came a small voice from beneath the excited hubbub. “The shelter’s on fire! Look!”

Sure enough, the rush of sparks through the smoke hole opening had been a little too fierce. The temperature of the air outside and the angle of the wind had driven some of the sparks down upon the outside of the shelter roof, enough to catch hold and ignite. And the flames from the fire had climbed a little too high and had caught the wooden edges of the smoke hole and begun to smoulder. Then, an extra gust of wind had been enough to billow the embers into life. Suddenly, we were no longer a crowd of excited children waiting for a seasonal treat. We were now a bunch of puzzled children sitting beneath a burning timber structure surrounded by a very flammable woodland.

Several of the adults amongst us leapt up and grabbed the fire buckets that stood at the corners of the shelter. The remainder of the parents tried to distract the children and keep them calm. But buckets of sand and water are fine when extinguishing a small fire at ground level. Not so useful when the fire is over your heads. It’s difficult to throw sand or water upwards. Despite the best efforts of the ground-based adults, they were failing to control the conflagration. Fire had gained a foothold and, unless some radical action was taken, the entire shelter roof would soon be ablaze. All eyes were now turned upwards, watching the drama unfold through a haze of wood smoke.

Suddenly, a red and white figure appeared from the smokey gloom. Abandoning a large, bulging sack at the edge of the shelter, the figure positioned a ladder against the roof edge and climbed up it onto the shelter roof. Children and adults alike moved quickly to the sandy ground around the outside of the shelter. From there we watched amazed as our parents passed buckets of sand and water up to the fat, bearded figure clothed in red who threw them, one after another, onto the encroaching flames. Our eyes were wide, our mouths agape as we saw what was happening. Father Christmas had come to put out the fire! Santa Claus had come to save us. It all made sense. Santa was used to working on roof-tops. After all, he delivered his presents by climbing down chimneys. This sort of thing must happen to him on a fairly regular basis. All in a night’s work. He must be used to dealing with fires. An expert at extinguishing them. Maybe that’s why he wears red – the colour of fire. Like fire engines and fire extinguishers.

It took a while, but slowly, surely Santa won his battle against the flames. Eventually he descended triumphant from a sodden, smokey rooftop to a messy puddle of sand and water where a fire had formerly blazed.

I cannot remember whether we ever received any presents from Father Christmas in the woods that year. It didn’t seem important. We got the best gift ever, a story to tell – The Night Santa Claus Saved Our Fire Shelter.

It is a story that speaks about our relationship with fire in a nuanced, balanced voice carrying notes of love, gratitude, warmth, care, respect, comfort, danger, loss, laughter and sadness. There is, clearly, in its telling, a living, personal relationship with fire. I do not see much of this kind of relationship evident in current reports about fire in mainstream media. Consider the statements below taken from www.euronews.com writing about fires in Greece.

“Overnight, a massive wall of flames raced through forests toward Alexandroupolis”

“The fires have removed wooded areas capable of absorbing 2.3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year.”

Or these taken from the BBC website,

“The fast-moving fire is bearing down on a city with a population of about 150,000 people”

“There were times when our staff were surrounded on all sides by fire,” says the chief. “They would not say they were ‘trapped’ but there’s no question it’s been dangerous. We saw dramatic fire behaviour, with winds ripping up trees by their roots and laying them down like toothpicks.”

Here, Fire is simply the villain of the piece. Notice that fire is personified in being vilified. It seems that we are quite comfortable to use language that implicitly recognizes fire as a living being as long as that being is a monster on which to confer blame. I would suggest that our ease with the personification of fire is a result of our deep-seated awareness that we do, indeed, have a relationship with fire. It goes back a long, long way. Back to our very beginnings. Without fire it is doubtful whether humankind would have survived as long as we have. Our ability to harness and control fire has enabled us to thrive and to spread to corners of the world where we would soon die without fire’s light and warmth. We are bound to fire. The old stories from around the world tell of this. In Greece, think Prometheus. Indigenous peoples around the world all had stories of how humankind got fire, most often as a gift from another intermediary being. Deep down we know that our relationship with fire is of defining importance to us.

So, whereas we are quick to paint fire as the bad guy in the case of wildfires, I see far less reporting on the other aspects of relationship with fire. Where in our modern world, do we make space to express gratitude to fire for all it gives?

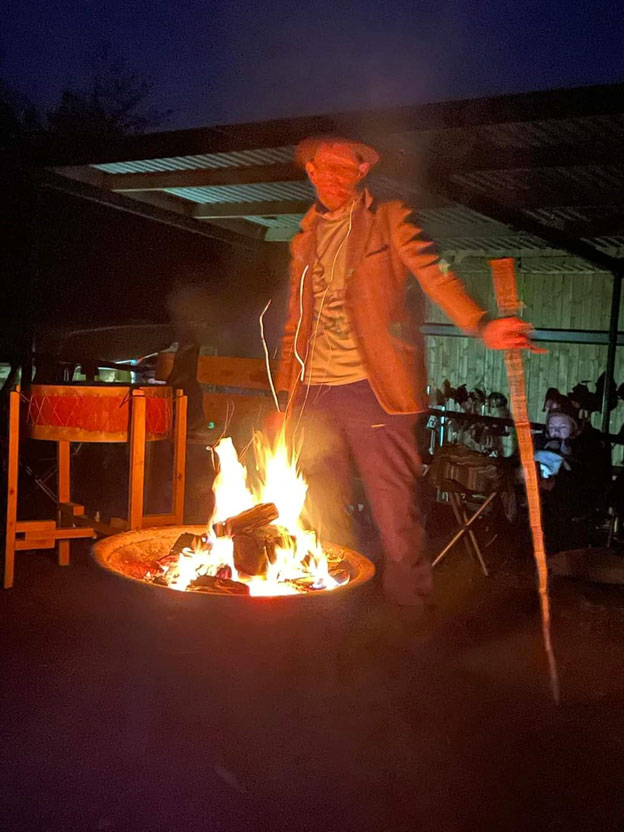

Photo Credit: Andy Jukes

We pay our energy bills and expect the lights to come on when we flick the switch, the stove to light when we want to cook a meal. Most of us take it for granted that we can have the benefits of fire whenever we desire and see no reason to express gratitude to what we have been taught to see as a resource available for our use. Suspend your judgement for a moment and try this thought experiment: Imagine that Fire is a living being, a person, with the same rights and expectations as yourself or any other human being. Would it be right to take all the gifts that Fire bestows, gifts without which we would die, without even a word of thanks? What would you predict might happen if this one-sided taking went on for years and years? Might we expect and even understand a little kickback from Fire?

In my view, the relationship with Fire that we in the modern world of instant light have been brought up to see as “normal” is, in reality, deeply flawed and does not serve us or any other beings well.

(This is the introduction to a longer work in progress entitled “Firekeeper” that explores the intimate and evolving relationship of the author with Fire.)

Andy Jukes is a writer, poet and artist based in the Shropshire borderlands between England and Wales. His work explores ordinary lives and places searching for their sacred heart.

Andy Jukes is a writer, poet and artist based in the Shropshire borderlands between England and Wales. His work explores ordinary lives and places searching for their sacred heart.

Andy’s latest book is Pan’s Footprints.

Andy’s latest book is Pan’s Footprints.