Listen to Bill Stovin read this article by Scott Lawrance (14:51)

“The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop. Together we will find the hope beyond hope, the paths which lead to the unknown world before us.”

– Dark Mountain Manifesto, 2007

“So what do you do if you find that you’re living at the end of a world? Firstly, the way you notice it is because the future doesn’t work anymore… Well, you can stop trying to make sense according to the logic of that world, according to its narratives. And you can start trying to create good ruins, trying to leave things behind that might turn out to be helpful to those who come after.”

“Don’t send me no more letters no

Not unless you mail them

From Desolation Row”

– Bob Dylan

Earth Day, April 22, 2023. Here in Cumberland a light rain falls. The temperature is almost five degrees lower than the average for this date. Yesterday, there was fresh snow on the hills. Lily, our little black Manx, is asleep in our room. She’s got the right idea. In an effort to avoid my second nap of the day, I check the Guardian for news of the planned mass protests in Britain being called a coalition of 200 organizations headed by Extinction Rebellion, including Avaaz, Friends of the Earth, and Keep Britain Tidy, among others. I find no new news. There is news about the impending Coronation, but no news about the hundreds of thousands projected to flood the streets to protest and to resist.

And are we not ourselves flooded with news, with data, information, statistics: fire, drought, flood, melting ice-caps, species loss, and an ever-increasing rise in carbon emissions, climate refugees. The list goes on. And with this glut of information, the invitation to despair. Lily, the Manx, rolls over onto her back, exposing her deliciously soft belly fur that invites caress. The palm of my hand delights in the tender warmth of her life. What are we to do?

There are many, of course, who deny the depth of the trouble. They assume and seek solutions. Science and technology will find solutions – “green technology”. Eminent futurist Michio Kaku, for example, believes in “unimaginable scientific and societal change,”that quantum computing will “will enable us to take CO2 out of the atmosphere and turn it into fuel, with the waste products captured and used again – so-called carbon recycling.” Along with Kaku, there are others, such as the Decarb Bros, “a loose affiliation of mostly young researchers, climate tech workers, policymakers and people following along online” who resist the “doomerism” that they feel is being propagated by such voices as Roger Hallam of Extinction Rebellion and Jem Bendell of Deep Adaptation.

Is there a middle way between the relentless optimism that seeks to preserve the status quo, to have both the jobs and the environment in which humanity continues to thrive, and the despair and anger felt by young climate activists like Greta Thunberg? This is the question explored by Dougald Hine in his recent book, At Work In The Ruins: Finding Our Place In The Time Of Science, Climate Change, Pandemics, and All The Other Experiences.

The book tracks his evolution from his first “own oh-fuck moment” as a climate activist in his late twenties to today, as he “works in the ruins” in his efforts to “grow a new culture” founded in community and conviviality. The journey begins with the realization that a narrow focus on climate change was inadequate in addressing the predicament within which we find ourselves, leading to questions “about how we got here in the first place, the nature and implications of the trouble we are in.”

The book tracks his evolution from his first “own oh-fuck moment” as a climate activist in his late twenties to today, as he “works in the ruins” in his efforts to “grow a new culture” founded in community and conviviality. The journey begins with the realization that a narrow focus on climate change was inadequate in addressing the predicament within which we find ourselves, leading to questions “about how we got here in the first place, the nature and implications of the trouble we are in.”

The climate crisis, he suggests, created conditions in which those of us blessed with all of the privileges of Modernity discovered those cracks in reality already experienced by multitudes in the Global South. The “end of the world” visited upon indigenous people everywhere began to seem possible even to privileged modernists like us. The reaction of Extinction Rebellion, Greta’s school strike, Just Stop Oil, Green New dealers and others to the paucity of response by world leaders to successive IPCC warnings about the climate emergency opened a space that seemed like an initiation, leaving people changed and disoriented. Why was nothing changing when so many could see what was happening?

Instead of focusing on the climate crisis as such, At Work consists of an inquiry into the nature of our predicament, seeking some answers to these questions. “How we got here?” occupies considerable space. The notion of “story” guides this enquiry. Dougald’s friend and colleague, Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, writes of “worlding stories”, stories as “living entities that emerge from and move things in the world.” In Hospicing Modernity, Vanessa suggests that we are currently “living off expired or expiring stories”, stories that while providing us with stability and direction are lethargic and stuck and are unable to any longer carry us forward in a good way. Before gesturing to an adequate response to our current predicament, a substantial part of At Work, the first four sections of the book, are devoted to clarifying the “story” that has brought us to this pass and holds us here.

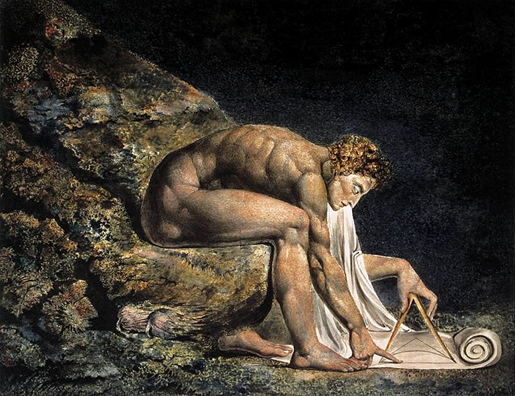

A central theme of this story, the story of “forward”, is the role of Science. We see the power and influence of Science in the injunction, in the context of both the climate crisis (think PPM – parts per million in emission measurements) and the recent pandemic (in which “following the science” led to many challenging policy decisions.) “In modern societies, science tells us what is real; it produces the kind of knowledge which has the right to be taken seriously and it is given a central role in the big stories these societies like to tell about the shape of history.” But Dougald suggests that those of us involved with other ways of knowing, ways that privilege the discernment of values, “need to show up…to enter into a relationship with science that respects its capacities and limits.” Predicaments such as ours call “for an exercise of judgement rather than the kind that can be answered through the process of observation, measurement and calculation.”

One indication of the limits of science is seen in the shock experienced by scientists as they discover how little the authority of this pre-eminent way of knowing has actually mattered when it comes to changes of political policy and social behaviour. (Since the first COP was convened in 1992, carbon emissions have steadily gone up, somewhere between 40 and 60%, depending on the source.) Reflections on the impact of COVID illustrate further challenges inherent in the reliance on Science as a guiding principle.

During said pandemic, as an immigrant to Sweden, Dougald found himself straddling two worlds, thus providing a unique perspective. While resisting the conspiratorial position of anti-vaxxers (and being vaccinated himself), he describes his sympathy for those resistant to follow the edicts driven by “the science”, noting that Sweden’s less restrictive position and that of most countries that followed stricter mandates both claimed to be grounded by such claims. Following Justin Smith’s reflections on Covid, which present an argument for mandatory vaccination, Dougald underscores the capitulation of intellectuals in favour of what he refers to as “STEMification,” a failure of public thinking in which the arts and humanities (‘human-centered enquiry and critique’) are subordinated to the higher status of science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

The roles of both Science and Modernity itself in the cultural clashes occasioned by the pandemic are masterfully brought home with reference to the work of Ivan Illich, the influential Roman Catholic priest, theologian, social critic, and author in the 1970s of such works as Deschooling Society. Illich was a particularly strong critic of the institutionalization of life, in the realms of education and medicine in particular, arguing that modern technologies and social arrangements undermine human values and human self-sufficiency, freedom, and dignity. One of the strongest arguments for lockdowns and other government mandated policies during the pandemic was the concern about overloading hospitals and long term facilities, both of which exemplify the shadow side of (even life saving) “progress.” The institutionalization of the tasks of healing and hospicing, previously located within the home or local community, necessitated a largely unprecedented population level response.

The roles of both Science and Modernity itself in the cultural clashes occasioned by the pandemic are masterfully brought home with reference to the work of Ivan Illich, the influential Roman Catholic priest, theologian, social critic, and author in the 1970s of such works as Deschooling Society. Illich was a particularly strong critic of the institutionalization of life, in the realms of education and medicine in particular, arguing that modern technologies and social arrangements undermine human values and human self-sufficiency, freedom, and dignity. One of the strongest arguments for lockdowns and other government mandated policies during the pandemic was the concern about overloading hospitals and long term facilities, both of which exemplify the shadow side of (even life saving) “progress.” The institutionalization of the tasks of healing and hospicing, previously located within the home or local community, necessitated a largely unprecedented population level response.

William Blake’s Newton with the Single Vision of Science, a brilliant mind separated from a sense of the Whole.

Having examined how we got here, At Work then proceeds to look to a response. It is now late April on Vancouver Island. Today is the first day of several forecast to have seen the sun and a full blue sky. It has been a long winter and a longer spring. There is a look of relief on people’s faces. Summer is coming! But with that feeling comes unbidden the thought “what fire might this summer bring us” and suddenly we shudder.

Associated concerns, worries, and fears prepare the ground for despair and hopelessness. But, as the Dark Mountain manifesto put it, “the end of the world is the end of the world as we know, not the end of the world full stop.”

In Hospicing Modernity, Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, describes three orientations to change, stances that organize how we think about possibilities going forward. Two of these orientations, referred to as soft- and hard-reform assume that the existing structures and ways of being, with sufficient tinkering, are sustainable. At Work is helpful in the unfolding of the third, beyond-reform, one form of which Vanessa refers to as “hospicing, which “recognizes the eventual inevitable end of modernity’s fundamentally unethical and unsustainable institutions, but sees the necessity of enabling a “good” death through which important lessons are processed.”

At Work suggests a fourfold path: salvage the good that can be taken from the “tangled legacy” of Modernity, mourn the good that cannot be taken with us, make use of the gift of discernment to see what was never as good as we thought it was, and to look for “dropped threads”, skills and knowledge that once we had, and that may still exist on the margins, that Ivan Illich referred to as “tools of conviviality.” There are myriad paths forward once we admit that the story we have lived by, the story of human mastery and infinite growth, no longer serves. In his closing chapters, Dougald suggests a few of the pathways forward – ways of knowing (epistemologies) and ways of being (ontologies) that have remained and arise from the margins. There are personal and policy (local, provincial, national and international) decisions to be made that are aligned with the birth of new, even currently unimaginable pathways “beyond reform”. GTEC Reader will continue to explore these pathways. “If the world is made of problems to be solved, then to admit you are out of solutions is to reach the end of the world…If there is hope today, I am convinced that it lies on the far side of such an admission, though the admission itself may feel like despair.” Meanwhile, may we develop the skills and practices that enable us, personally and collectively to slow down, stay with the trouble and take care of each other. May our love for the more than human world lead us forward.

Scott Lawrance, Ed.D., R.C.C.

Scott Lawrance, Ed.D., R.C.C.

A retired member of the B.C. Teacher’s Federation, Scott has taught at all levels of public education from grade two to post-Secondary. His current professional interests include Buddhist approaches to eco-therapy. Scott and his Salish Sea Eco-retreats partner, Tara Souch offer annual eco-retreats for wilderness guides and interested professionals. He is the author of four books of poetry and has, in the past, edited two poetry magazines, “Raven” and “Circular Causation”.