Book Review by Ross Thrasher

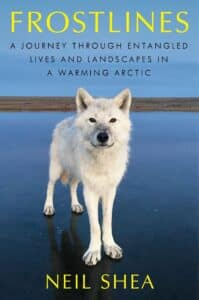

Frostlines: A Journey Through Entangled Lives and Landscapes In A Warming Arctic, by Neil Shea. Ecco/HarperCollins, 2025.

National Geographic writer Neil Shea has crafted an elegy for the traditional world of the Far North. In the 200 pages of Frostlines he travels with Indigenous guides across the Canadian Arctic, Alaska, Greenland and Norway in search of the migratory wildlife that roams these vast frozen regions. Each of the six chapters features a different Arctic location and a different nomadic species.

The author notes that Canada’s northernmost archipelago consists of no fewer than 32,000 islands, with only 20,000 human inhabitants. On Ellesmere Island, just west of Greenland and north of Baffin Island, he follows a family of Arctic wolves who are hunting muskoxen across the tundra. The area is so remote, so devoid of people, that the wolves are neither aggressive nor frightened of him, enabling close observation.

Rapid change is a recurring theme in this conversational account of life in the harsh northern environment, to which Shea has returned many times over the years. “The Arctic I saw in 2005 no longer exists.” For example, the fabled Northwest Passage through Canada’s Arctic islands, linking the Atlantic and the Pacific, had always been an ice-choked obstacle that sank the dreams and lives of many explorers. But now, as the air and water get warmer and the ice melts, every summer dozens of ships complete that inter-oceanic voyage.

The annual caribou migrations on the mainland of Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and Alaska have been among the largest and longest of any species on the planet. Half a dozen huge caribou herds have traversed different regions of Canada’s north and Alaska, but in recent years the population of some herds has crashed. Among the alleged culprits: diseases, wolves, over-hunting by humans, and mining infrastructure (roads, fences, open pits) that can interfere with the caribou’s migration routes. The author also claims that “warming is heavily implicated in the great vanishing” of the caribou, with changes in vegetation, wetter and warmer winters affecting the herds’ access to food. He visits two Indigenous communities who still rely on hunting caribou for meat and hides, but are finding it harder every year to locate the animals. The author asks: “What happens to a caribou people who lose their caribou?”

It’s interesting to note that polar bears, perhaps the most visible victims of climate change in today’s warming Arctic, are hardly mentioned in this book. However their struggle for survival on melting pack ice has been well documented elsewhere.

Arriving on Greenland, Shea is confronted with a historical mystery. What happened to the Norse settlers who arrived on the island from Northern Europe around 1000 A.D. and disappeared 400 years later? For centuries they fished, established farming communities and also hunted walruses for their ivory tusks, which were prized in the Old Country. One theory of the Norse extinction is climate-related: a Little Ice Age in the fifteenth century could have resulted in the collapse of agriculture on Greenland, prevented supplies from arriving by ship from Europe, and led to the departure of fish and marine mammals. Perhaps starvation followed. Nowadays Greenland is mainly populated and governed by the Inuit, whose ancestors first reached the island some time after the Norse people! Clearly they were more adaptable than the European immigrants who preceded them.

In the final chapter of Frostlines the author visits Kirkenes, a town at the top of Norway close to the Russian border. Here he sees herds of reindeer, “the slightly smaller cousins of caribou”, wandering around, and describes them as “semidomesticated” by the Indigenous Sami people. In Kirkenes Shea also learns about recent human migrations — thousands of Syrians, Africans and other refugees who crossed into Norway after the Russians annexed Crimea in 2014. They had already escaped authoritarian regimes in their home countries, and were desperate to evade another one.

Frostlines offers a lyrical indictment of modern society’s destructive appetites:

“Colonialism and capitalism … [are] still at work all over the world, eating what’s left, digging for more, denying the entangled crises of climate and extinction.” The recent geopolitical wrangling over Greenland confirms this assessment. Traditional ways of life are under threat for humans and other inhabitants of the Arctic, but this book eloquently depicts their resilience.

Ross Thrasher

Ross has enjoyed a 30-year career as a librarian at post-secondary institutions in Canada, the U.C. and the South Pacific. Most recently he served for eight years as Library Director at Mount Royal College in Calgary, leading the library’s transition to university status. In retirement Ross maintains an active interest in literature, travel and the performing arts.

Read more book reviews in GTEC’s Communications & Media section here.